Potentially Preventable Hospitalisations; identifying hotspots of inequalities

A Geographic and Temporal Analysis

Published: 2019

Introduction

The level of Potentially Preventable Hospitalisations (PPHs) is an accepted measure of health system performance and, despite its limitations, can geographically highlight areas of concern where rates of hospitalisation are high or to investigate why in other instances rates are low.

This study identifies the geographic and temporal persistence of PPHs across Australia, over the period from 2012/13 to 2016/17. It follows on from work by Duckett and Griffiths (2016) published as “Perils of Place: identifying hotspots of health inequalities”. This study provides a framework to identify the existence of areas with persistently high PPH rates over time known as “PPH hotspots” and provides core principles to highlight areas where interventions can be targeted. We hope that this new analysis, and its presentation in geographical maps, heat map graphs and data sheets, will provide information that is useful to the various levels of the health system, from state and territory health agencies to local and regional health networks and boards, PHNs and primary care practitioners, in working together with an aim to reducing the level of PPHs through improved primary health care outcomes at the local area level.

The interpretation of the data and its presentation is complex, and we encourage users to read the comprehensive notes at the links presented below, and in particular to take note of the sections on Limitations and Using the Atlas. Further information can be obtained by contacting PHIDU.

Justin Beilby, a health services researcher and general practitioner for over 30 years provides his insights on the usefulness of PHIDU’s hot spot analysis of potentially preventable hospitalisations for health care decision making.

Detailed notes on Potentially Preventable Hospitalisations

Summary

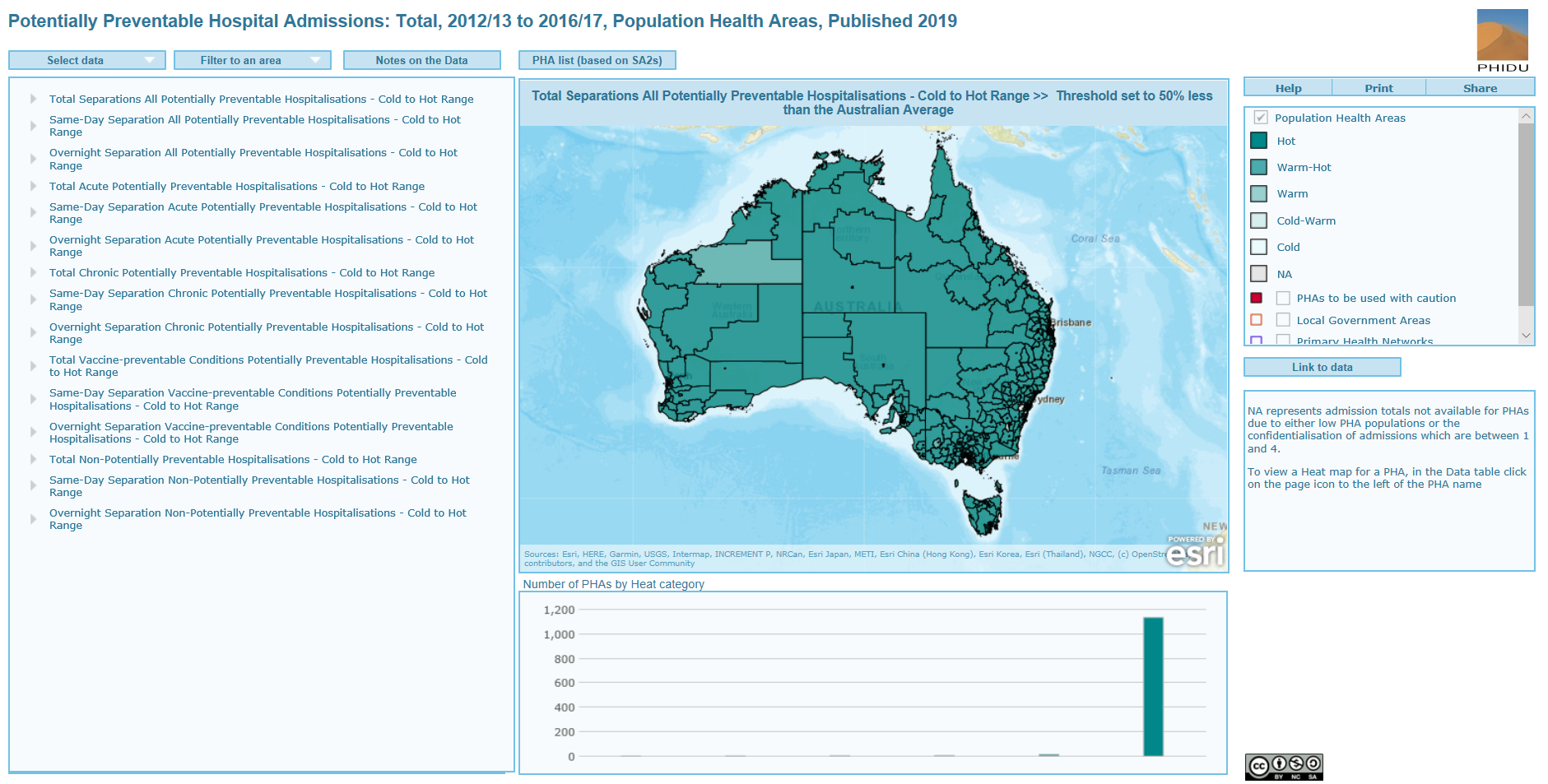

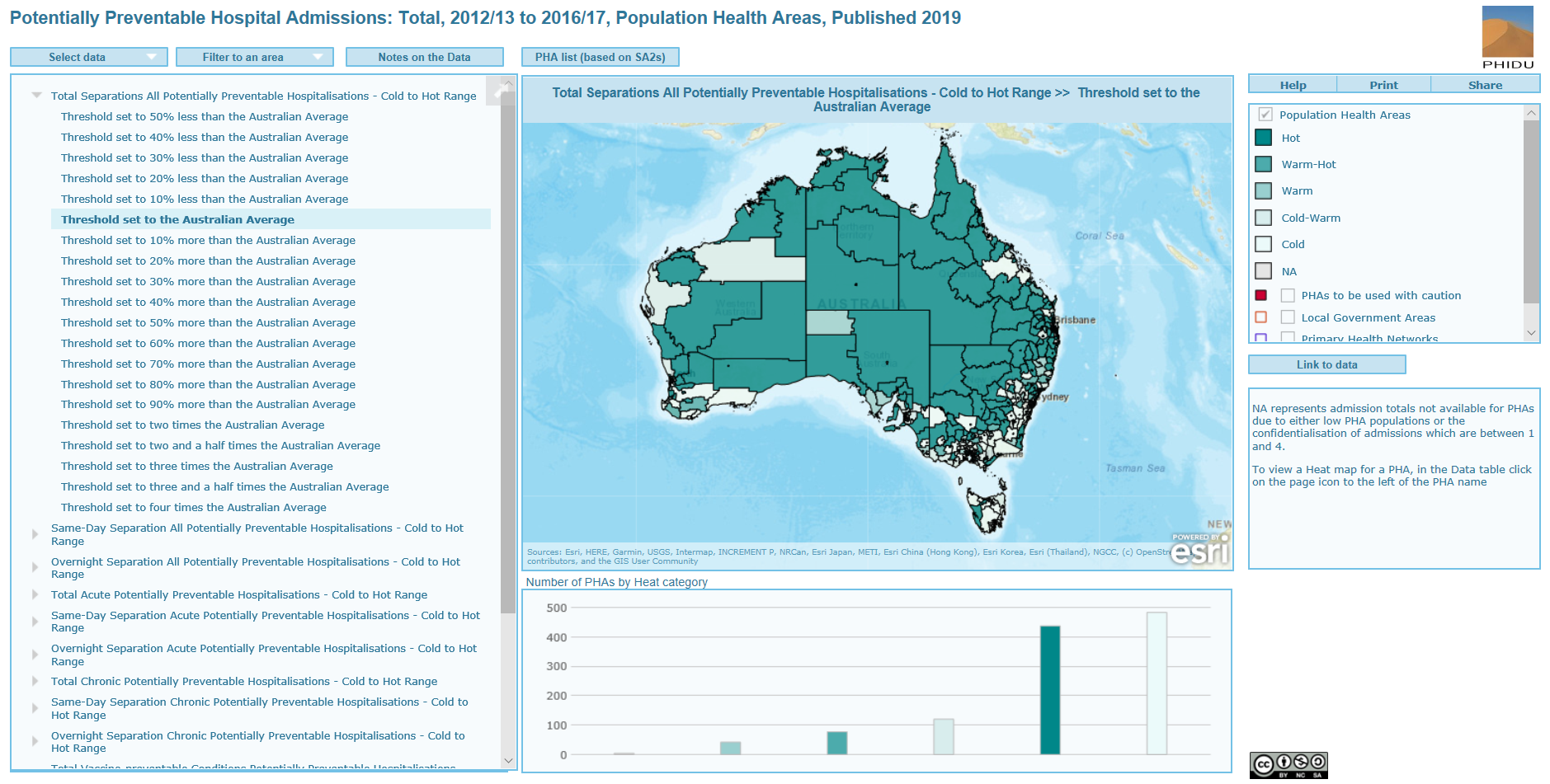

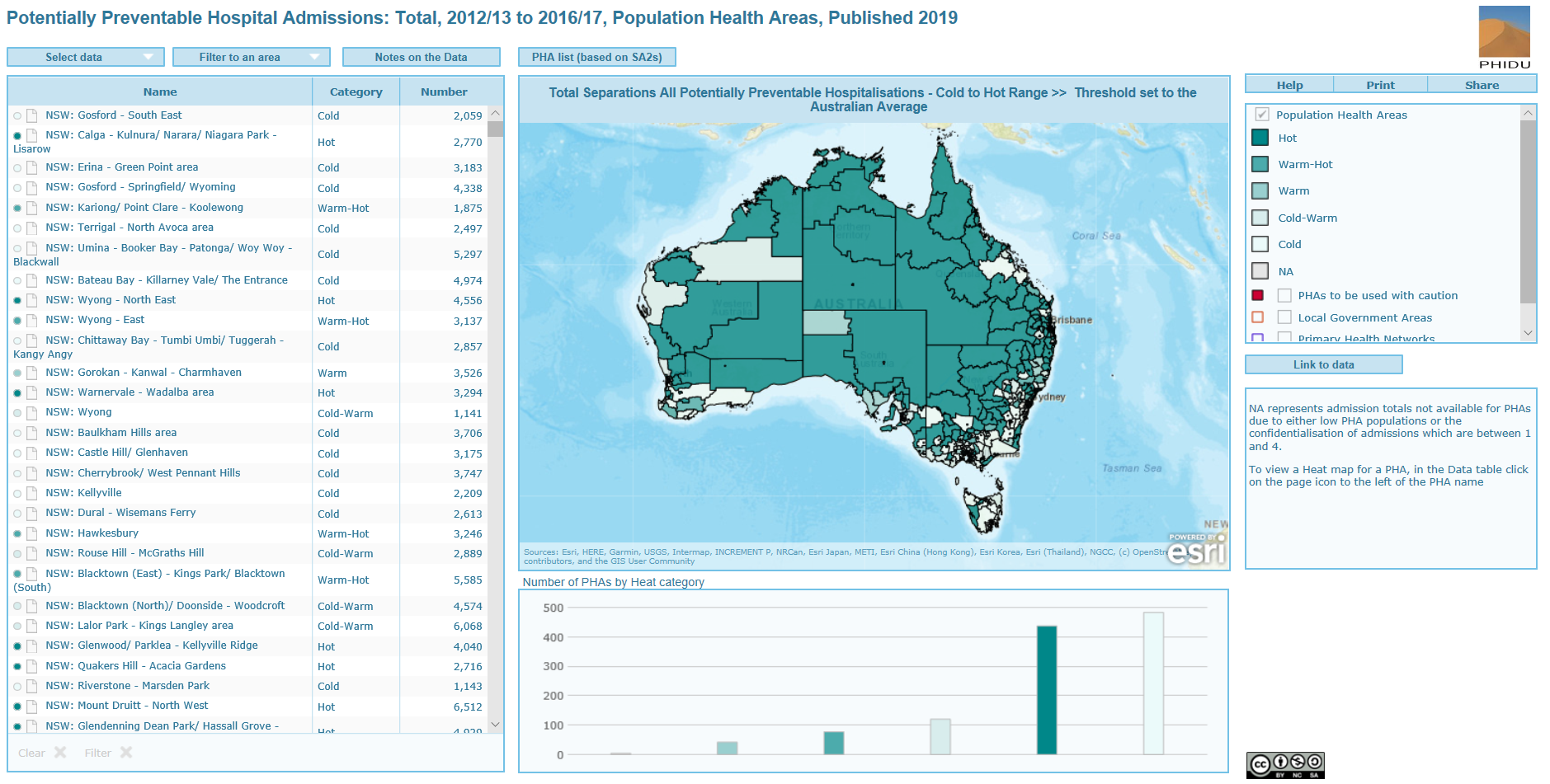

The atlases show the geographic and temporal variation in the rates of PPH by category and conditions, over the period from 2012/13 to 2016/17. By providing a range of thresholds we can easily investigate the sensitivity in the differences between geographic areas, both between (geographic) and within (temporal) Population Health Areas (PHAs) compared to the Australian average. Rates will vary by geographic area, category or condition and over time. We must also highlight that when specific conditions are investigated, the number of admissions by PHA may be small. Thus, we suggest that you use these data with caution.

Analysing the temporal trend of the Total Separations in the All PPH category provides an overview of the distribution of the overall rate of PPH admissions. It is worth noting that the Total Separations in the All PPH category across the PHAs will be made up of different combinations of Acute, Chronic and Vaccine-preventable conditions and same-day and overnight hospital separations. This suggests that, once this complexity is unpacked, different strategies will need to be implemented to effect change.

A total of 68 PHAs were deemed “Hot” for Total Separations in the All PPH category when compared to the 50% more than the Australian average threshold. Table 1 shows the list of PHAs as the thresholds decrease from the highest threshold, the four times greater than the Australian average to the 50% more than the Australian average threshold. The PHAs are shown once against their cut-off thresholds, i.e. PHAs in the four times greater threshold are hot for this threshold and below.

Two PHAs in the Northern Territory are the hottest in Australia with rates consistently over four times the Australian average. There were no new or additional PHAs in the three and half times the Australian average category, while the remote areas of Queensland and Western Australia comprise the majority of “Hot” PHAs with rates consistently over the 70% more than the Australian average threshold.

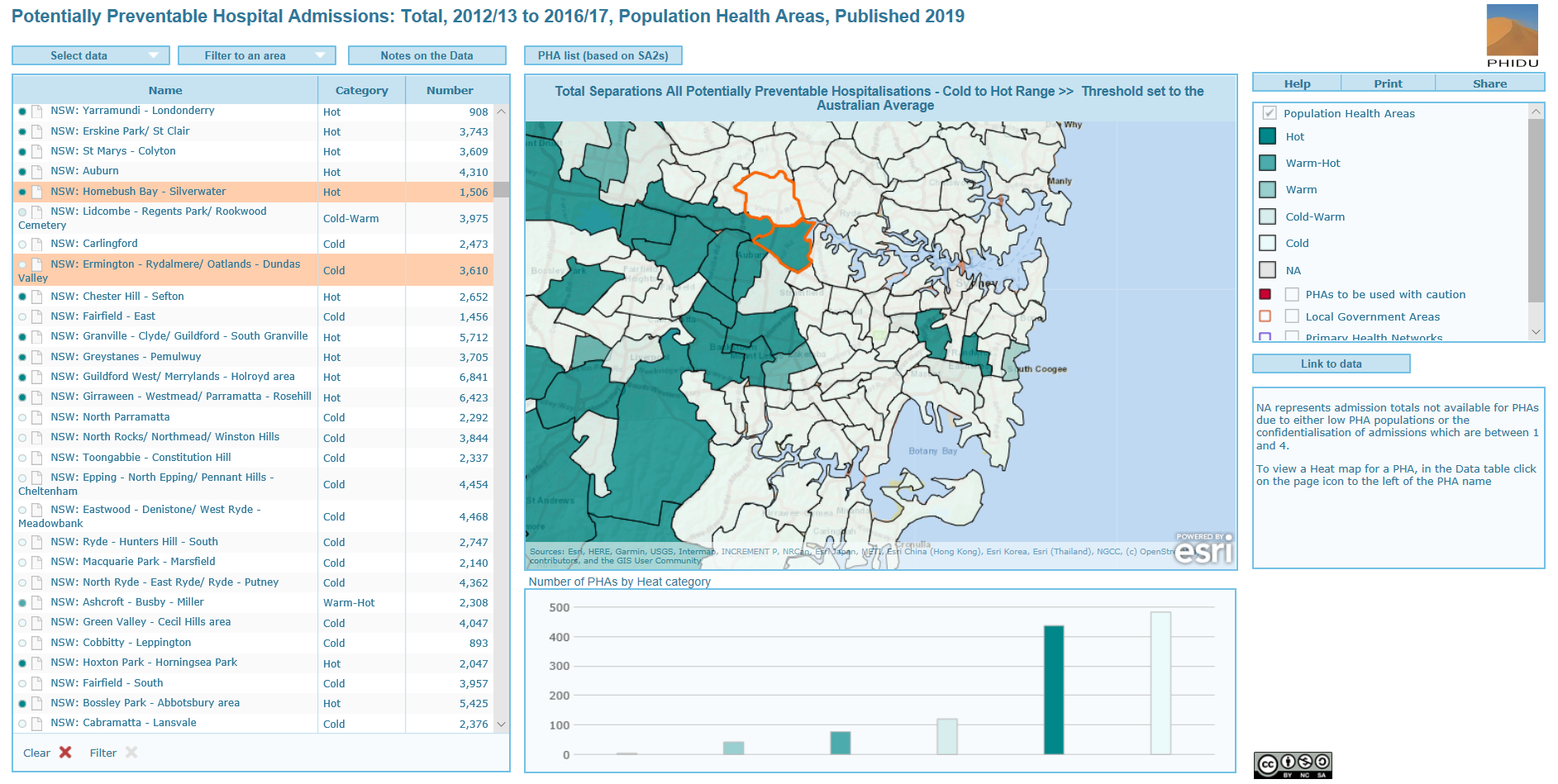

The geographic and temporal variation for all PHAs across Australia can be viewed here. The value of providing a range of thresholds can be shown when we investigate the heat of Total Separation for the All PPH category by capital city at the 50% more than the Australian average. For example, the map for Brisbane shows a clustering of “Hot” PHAs in the north and west of the city while, for Perth, PHAs are shown as “Cold” rather than ”Hot” for this threshold. At the national level, PHAs in Perth could be interpreted as having no issues with PPHs. However, this may reflect more of an issue with the choice of threshold used, since the presence of “Hot” PHAs in Perth does not occur until the threshold is reduced to 30% more than the Australian average.

For the Total Separations in the All PPH category, PHAs in the 80% more to the four times greater than the Australian average threshold categories reported “Hot” values in a majority of instances – for all PHAs in the Acute and Chronic PPH categories with the exception of WA: Newman, which reported cooler values for the Chronic condition category for these thresholds. More variation was found in the Vaccine-preventable PPH category with the nine PHAs in the two and a half times and above categories classified as “Hot” for the Vaccine-preventable category. This however varied by threshold across the PHAs in the Vaccine-preventable PPH Atlas for Total Separations in the All PPH category. The list of PHAs which were deemed “Hot” for the 50% more and above thresholds are available in the Acute and Chronic PPH category tables. The geographic and temporal variation for these thresholds and categories for Australia can be viewed in the Acute and Chronic PPH atlases.

Alternatively, highlighting PHAs which have been deemed “Cold” provides an understanding of where issues do not exist. A total of 123 PHAs were deemed “Cold” when compared to the 20% less than and below the Australian average thresholds for Total Separations in the All PPH category. Table 2 provides a list of PHAs from the 50% less to the 20% less categories. The PHAs are shown once against their cut-off thresholds, i.e. PHAs in the 50% less than the Australian average threshold are cold for this threshold and above.

The geographical and temporal variation of these PHAs can be viewed here. When the threshold is decreased to the 30% less category, the number of PHAs is reduced to 31.

As with the PHAs reported as “Hot”, PHAs deemed “Cold” for the Total Separations in the All PPH category were also “Cold” for the PHAs in the Acute and Chronic PPH atlases. Once again, a different distribution was found for the Vaccine-preventable PPH category with the majority of these 123 “Cold” PHAs becoming hotter.

The value of providing a range of thresholds can be again shown when we investigate the lack of heat of the Total Separations in the All PPH category by capital city at the 20% less than the Australian average. For example, in Sydney there is a distinct clustering of “Cold” PHAs in the Harbour side PHAs, whereas in Adelaide the majority of the metropolitan area was deemed as “Hot’. Changing the threshold to 10% less than the Australian average highlighted a clustering of “Cold” PHAs in the eastern and south-eastern part of the metropolitan area.

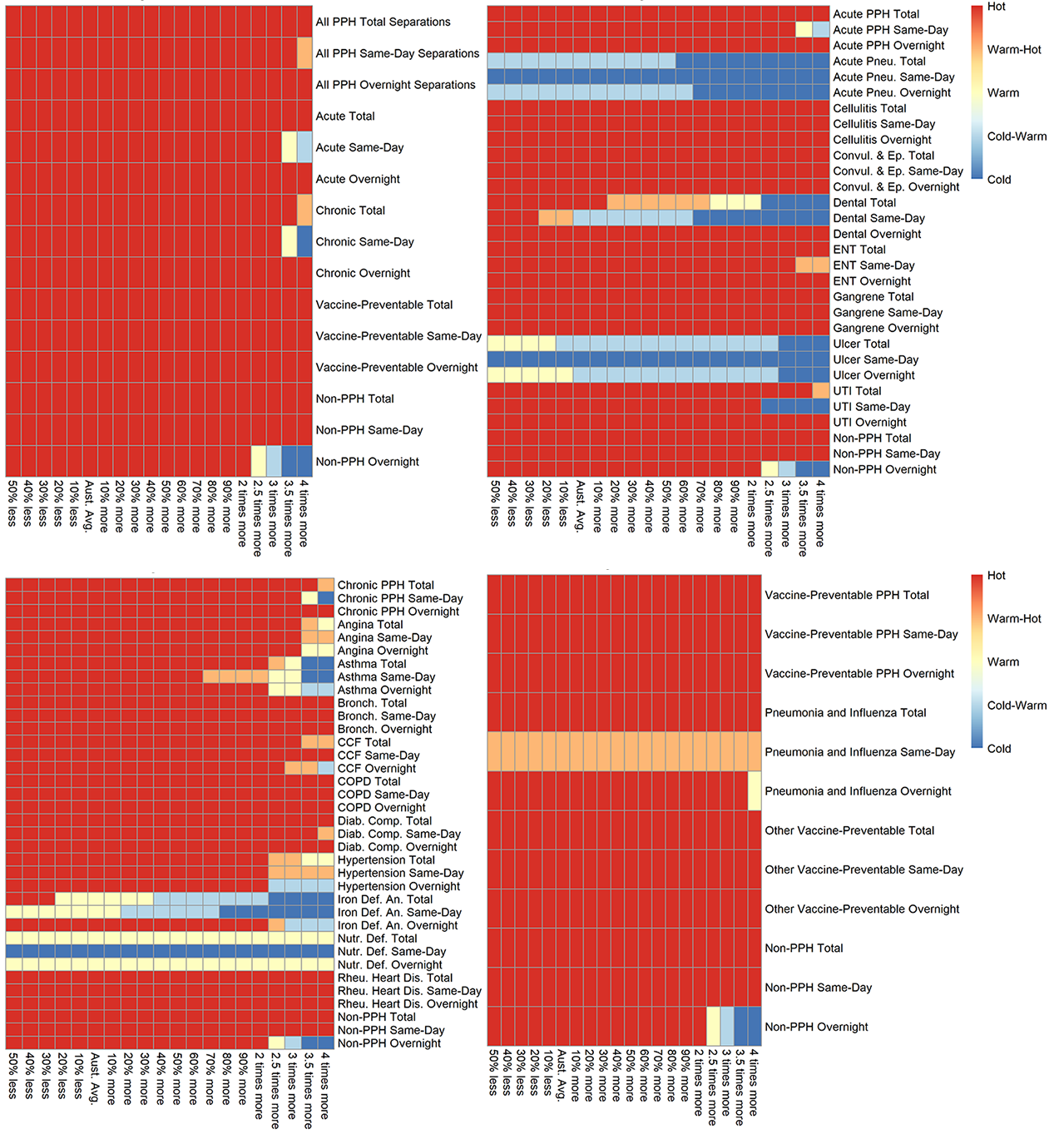

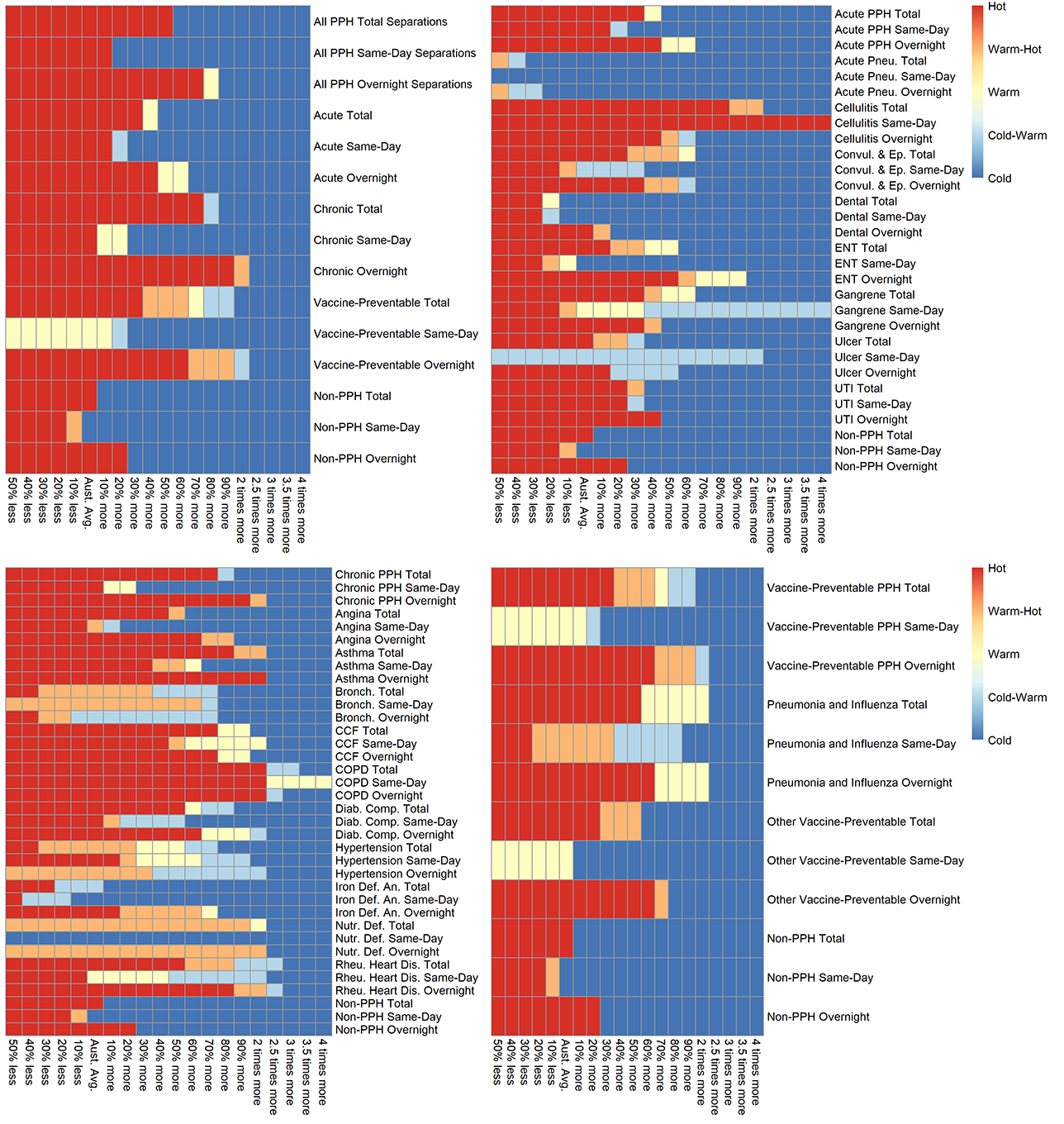

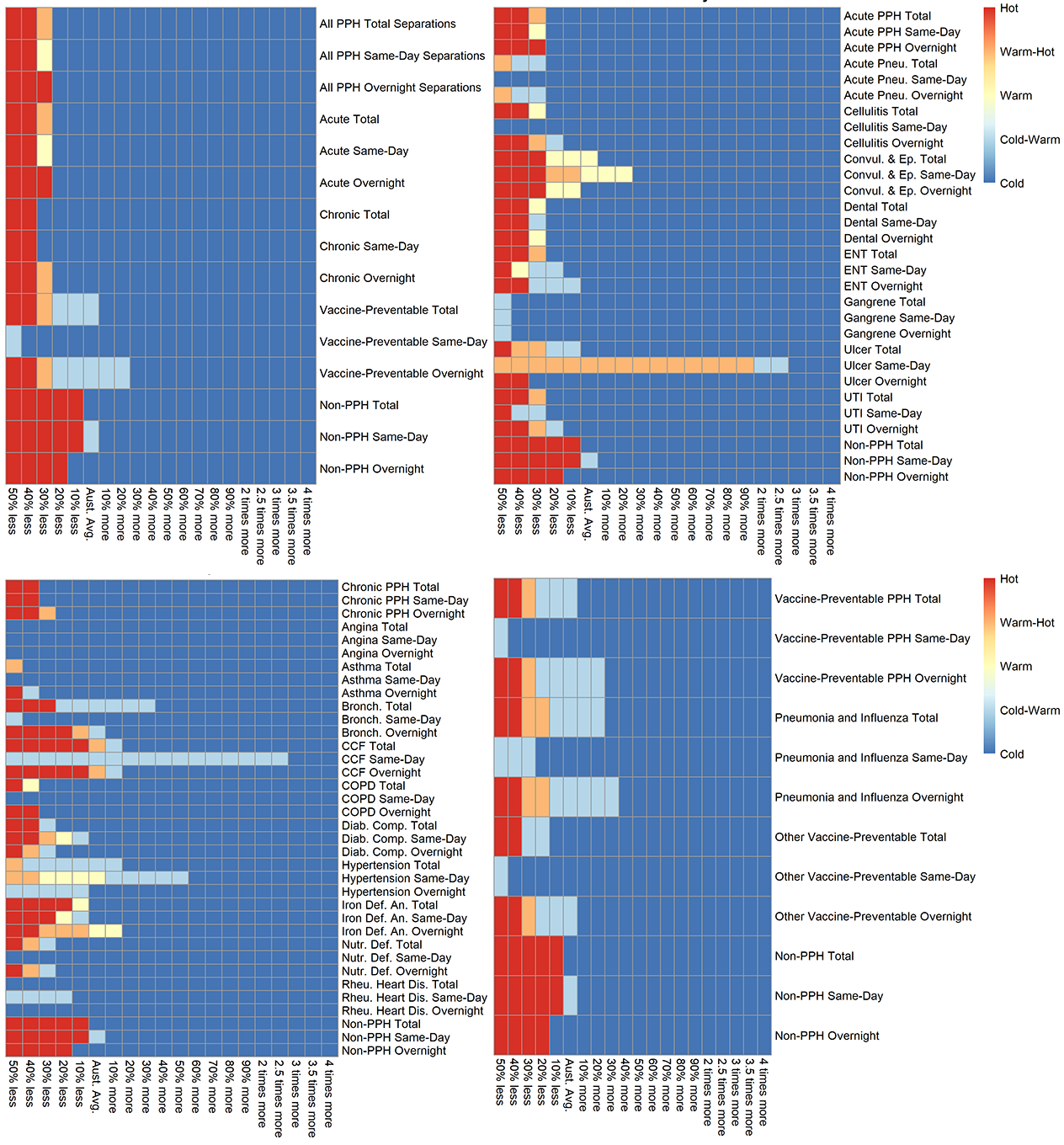

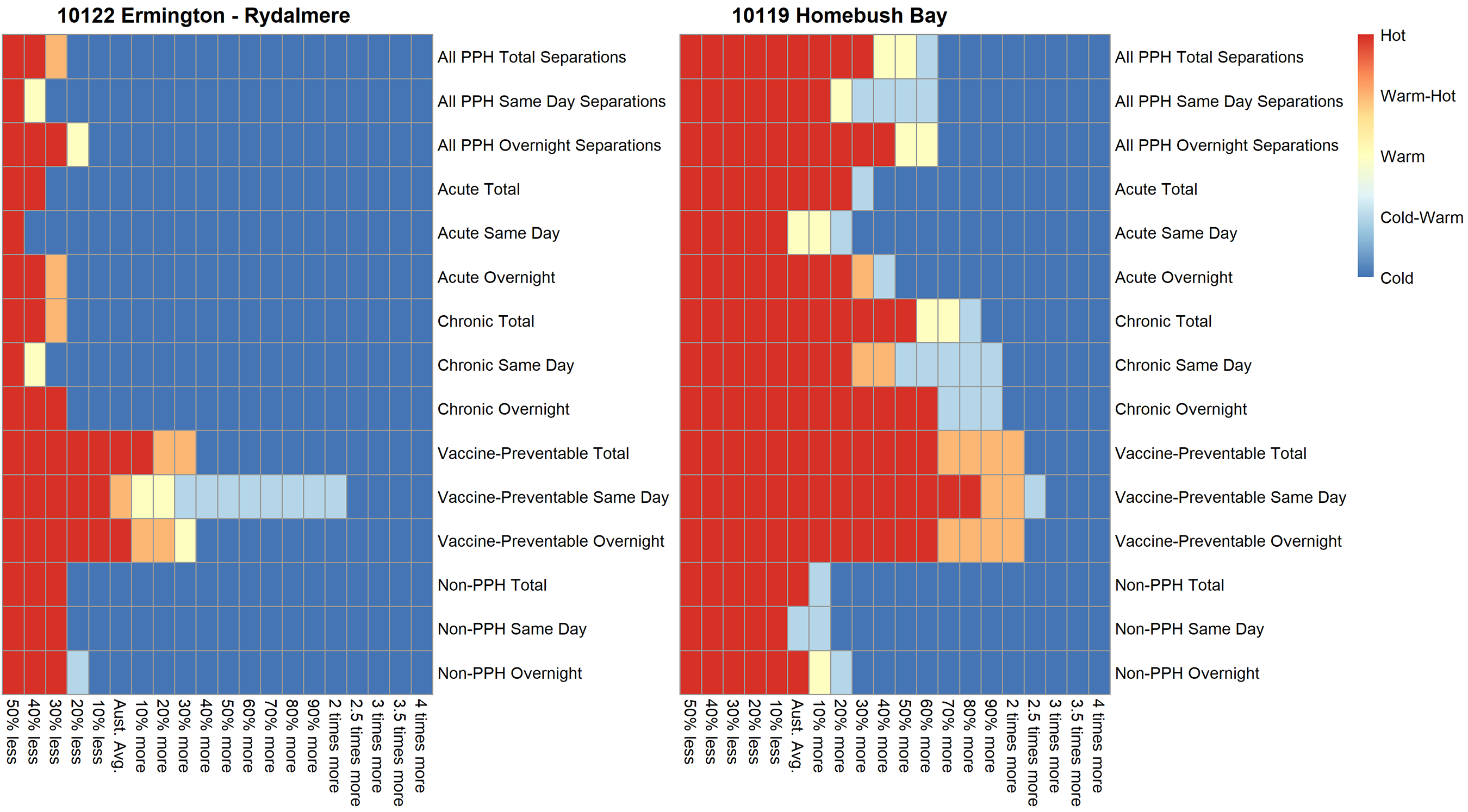

The lists of PHAs can also be investigated singularly using a heat map graph. These graphs show a visual representation of the heat of a PHA by threshold and category and condition when a specific PPH category is selected. The heat maps can be accessed by following the instructions in the Heat map graphs by PHA section.

We selected the NT: Barkly/ Tennant Creek PHA, NSW: Mount Druitt – Whalan and NSW: Canada Bay – East PHAs to show the complex interactions of conditions and their influence on the variation in heat across Australia.

The heat map graphs for the “Hottest” PHA, the NT: Barkly/ Tennant Creek PHA show the variation in heat across all PPH categories and conditions (Figure 1). The majority of categories and conditions are “Hot” across all thresholds. This includes the non-PPH categories which are used as a proxy indicator for health status within the PHA. In this case the PHA’s health status is deemed low. Rates for some conditions, such as Dental and Ulcer conditions, are cooler, indicating that rates are consistently lower than the Australian average. It is important to note that while rates for Acute Pneumonia (non-vaccine-preventable), Iron Deficiency Anaemia and Nutritional Deficiency are low, this may be a function of the rarity of the condition across Australia.

The heat map graphs for the NSW: Mount Druitt – Whalan PHA show the variation in heat across all PPH categories and conditions (Fig. 2). Chronic conditions make up the highest level of heat followed by Vaccine-preventable and Acute PPH categories. Rates of overnight separations are consistently higher than the Australian average for all PPH categories. For Acute conditions, Cellulitis, particularly for same-day separations, and Overnight separations for ENT, Convulsions and Epilepsy, and Gangrene are consistently higher than the Australian average. Numerous Chronic conditions such as COPD, Asthma, and Diabetes complications are above the Australian average, once again particularly for Overnight separations. Rates for Rheumatic Heart Diseases are higher than the Australian average, with 25 admissions for the PHA over the five years (see Chronic PPH Atlas, Total Rheumatic Heart Diseases). While the rate is higher than the Australian average, this small number “may” only represent only a handful of people being admitted multiple times over the five years. Care must therefore be taken when interpreting indicators with low numbers of admissions. Both Vaccine-preventable conditions have rates consistently higher than the Australian average. The health status indicator for the PHA (non-PPH conditions) suggest the PHA is near the Australian average, although the Overnight separations indicator is higher than the Australian average.

The heat map graphs for the NSW: Canada Bay – East PHA show the variation in heat across all PPH categories and conditions (Fig. 3). Rates of admission across all PPH categories are significantly lower than Australian average. This result is similar for the majority of conditions other than for the Chronic condition of CCF (Congestive Cardiac Failure) which is near the Australian average. Interestingly, the Acute condition Ulcer same-day separation shows a “Warm-Hot” value for thresholds above the Australian average. Once again, caution must be taken with interpreting these results, as the overall rarity of same-day admissions for this condition, together with a slightly higher number of admissions in the PHA when compared to other PHAs (n=9) has caused this finding. The indicator for the PHA health status is near the Australian average.

For the selection of PHAs above, the results suggest that we can focus on PPH categories or specific conditions which have been highlighted as issues in the PHA. We can also have less focus on those conditions which are highlighted as not a high priority. Investigating each PHA singularly also leads to addressing whether this same condition is high or low in neighbouring PHAs. This clustering of PHAs with high or low heat for a condition can then be explored directly within the specific atlases.

| Magnitude of threshold greater than the Australian Average | Population Health Areas (PHAs) |

| Four times | NT: Alice Springs – Remote, NT: Barkly/ Tennant Creek |

| Three times | Qld: Carpentaria/ Mount Isa Region/ Northern Highlands, WA: Derby – West Kimberley/ Roebuck, WA: Halls Creek/ Kununurra |

| Two and half times | SA: Coober Pedy/ Outback, NT: Alice Springs – Town, NT: Anindilyakwa/ East Arnhem/ Nhulunbuy, NT: Elsey/ Gulf/ Victoria River |

| Two times | NSW: Bourke – Brewarrina/ Walgett – Lightning Ridge, Qld: Kuranda/ Mareeba, Qld: Far North, Qld: Bundaberg/ Bundaberg North/ Millbank area, WA: Broome, WA: South Hedland, NT: Katherine |

| 90% | Qld: Charleville/ Far Central West/ Far South West, SA: Renmark, WA: Newman |

| 80% | Qld: Babinda/ Innisfail/ Yarrabah, Qld: Berserker/ Lakes Creek/ Rockhampton City, SA: Flinders Ranges/ Port Augusta, WA: Meekatharra, Tas: Acton – Upper Burnie/ Burnie – Wivenhoe |

| 70% | NSW: Glendenning Dean Park/ Hassall Grove – Plumpton, Qld: Inala – Richlands/ Wacol, Qld: Browns Plains/ Crestmead/ Marsden, Qld: Logan Central/ Woodridge Qld: Caboolture, Qld: Manoora/ Manunda/ Westcourt – Bungalow/ Woree, Qld: Barcaldine – Blackall/ Longreach, Qld: Kingaroy Region – North/ Nanango, Qld: Maryborough (Qld)/ Tinana, SA: Elizabeth/ Smithfield – Elizabeth North, NT: Daly – Tiwi – West Arnhem |

| 60% | NSW: Cobar/ Coonamble/ Nyngan – Warren, Vic: Broadmeadows, Vic: Bendigo, Qld: Rocklea – Acacia Ridge, Qld: New Chum/ Redbank Plains, Qld: Kingston/ Slacks Creek, Qld: Aroona/ Caloundra – Kings Beach/ Moffat Beach, SA: Port Pirie, SA: Millicent, WA: Kalgoorlie, Tas: Mornington – Warrane |

| 50% | NSW: Mount Druitt – Whalan, NSW: Moree Region/ Narrabri/ Narrabri Region. NSW: Griffith Region, NSW: Leeton/ Narrandera, Vic: Cranbourne/ Cranbourne West, Qld: Chermside, Qld: Bundamba/ Riverview, Qld: Ipswich – Central/ North Ipswich – Tivoli, Qld: Bethania – Waterford/ Loganlea/ Waterford West, Qld: Balonne/ Goondiwindi/ Inglewood – Waggamba/ Tara, Qld: Bouldercombe/ Gracemere/ Mount Morgan, Qld: Burnett – North, SA: Davoren Park, SA: Ceduna/ West Coast (SA)/ Western, WA: Carnarvon, WA: Boulder/ Kambalda – Coolgardie – Norseman, WA: Leinster – Leonora, WA: Geraldton/ Geraldton – East, WA: Roebourne, WA: Katanning, NT: Darwin – Marrara/ Berrimah area, NT: Driver/ Gray/ Moulden/ Woodroffe |

Note: The PHAs are shown once against their cut-off thresholds, i.e. PHAs in the four times greater threshold are hot for this threshold and below.

| Less than the Australian Average | Population Health Areas (PHAs) |

| 50% | Tas: West Ulverstone |

| 40% | NSW: Canada Bay – West, Tas: Legana/ Riverside/ Trevallyn, Tas: Burnie - Ulverstone Region, Tas: North West/ Waratah |

| 30% | NSW: Sydney - Haymarket - The Rocks, NSW: Burwood – Croydon, NSW: Ermington - Rydalmere/ Oatlands - Dundas Valley, NSW: Fairfield – East, NSW: Toongabbie - Constitution Hill, NSW: Engadine - Loftus/ Heathcote – Waterfall, NSW: Oyster Bay/ Sutherland area, Vic: Thornbury, Vic: Docklands/ Southbank/ West Melbourne, Vic: Albert Park, Vic: Bulleen/ Doncaster, Vic: Doncaster East, Vic: Templestowe/ Templestowe Lower, Vic: Hughesdale, Vic: Ballarat – North, Qld: St Lucia, SA: APY Lands, WA: Busselton Region, Tas: Newstead/ Norwood (Tas.)/ Youngtown – Relbia, Tas: Grindelwald - Lanena/ Hadspen – Carrick, Tas: Triabunna – Bicheno, ACT: Gungahlin - South |

| 20% | NSW: Baulkham Hills area, NSW: Cherrybrook/ West Pennant Hills, NSW: Dural - Wisemans Ferry, NSW: Riverstone - Marsden Park, NSW: Marrickville, NSW: Glebe - Forest Lodge/ Pyrmont – Ultimo, NSW: Double Bay area, NSW: Dover Heights/ Rose Bay - Vaucluse - Watsons Bay, NSW: Mortdale - Penshurst/ Peakhurst – Lugarno, NSW: South Hurstville - Blakehurst area, NSW: Riverwood, NSW: Canada Bay – East, NSW: Leichhardt – Annandale, NSW: Ashfield, NSW: Canterbury (North) - Ashbury area, NSW: Dulwich Hill - Lewisham/ Haberfield - Summer Hill, NSW: Chatswood area, NSW: Lane Cove - Greenwich/ St Leonards – Naremburn, NSW: Willoughby - Castle Cove – Northbridge, NSW: Hornsby – Waitara, NSW: Normanhurst - Thornleigh – Westleigh, NSW: St Ives/ Turramurra/ Wahroonga – Warrawee, NSW: North Sydney - Mosman – West, NSW: Blackheath - Megalong Valley/ Katoomba – Leura, NSW: Blue Mountains - North Region, NSW: Ermington - Rydalmere/ Oatlands - Dundas Valley, NSW: North Rocks/ Northmead/ Winston Hills, NSW: Toongabbie - Constitution Hill, ,NSW: Epping - North Epping/ Pennant Hills – Cheltenham, NSW: Ryde - Hunters Hill – South, NSW: North Ryde - East Ryde/ Ryde – Putney, NSW: Cobbitty – Leppington, NSW: Cabramatta – Lansvale, NSW: Canley Vale - Canley Heights/ Fairfield, NSW: Caringbah - Lilli Pilli, NSW: Cronulla - Miranda - Caringbah – West, NSW: Engadine - Loftus/ Heathcote – Waterfall, NSW: Oyster Bay/ Sutherland area, NSW: Cooma Region/ Jindabyne – Berridale, NSW: Dubbo Region, NSW: Bowral/ Robertson - Fitzroy Falls, NSW: Mittagong, NSW: Moss Vale – Berrima, Vic: East Melbourne/ South Yarra – West, Vic: Carlton North - Princes Hill/ Fitzroy North, Vic: Hawthorn/ Hawthorn East, Vic: Bulleen/ Doncaster, Vic: Doncaster East, Vic: Templestowe/ Templestowe Lower, Vic: Brighton (Vic.)/ Brighton East, Vic: Hughesdale, Vic: Ivanhoe East – Eaglemont, Vic: Eltham, Vic: Strathmore, Vic: Bendigo Region – South, Vic: Lorne - Anglesea/ Torquay, Vic: Ocean Grove - Barwon Heads/ Queenscliff, Vic: Seymour Region, Qld: Centenary – West, Qld: Kenmore - Brookfield - Moggill – West, Qld: Chapel Hill/ Fig Tree Pocket/ Kenmore, Qld: Indooroopilly/ Taringa, Qld: Samford Valley, SA: Aldgate - Stirling/ Uraidla – Summertown, SA: Glenside - Beaumont/ Toorak Gardens, SA: Grant, SA: Naracoorte Region, WA: Cottesloe - Claremont – Central, WA: Duncraig/ Hillarys/ Sorrento – Marmion, WA: Joondalup - North Coast, WA: Stirling – West, WA: Armadale – West, WA: Forrestdale - Harrisdale - Piara Waters, WA: Canning – South, WA: Bull Creek/ Leeming/ Murdoch – Kardinya, WA: Albany - South-East or Albany – Region, Tas: Kingston - Huntingfield/ Margate – Snug, Tas: Kingston Beach/ Taroona area, Tas: Hobart/ Lenah Valley - Mount Stuart/ West Hobart ,Tas: Mount Nelson/ Sandy Bay/ South Hobart area ,Tas: Newstead/ Norwood (Tas.)/ Youngtown – Relbia, Tas: Prospect Vale – Blackstone, Tas: Beauty Point – Beaconsfield ,Tas: Cygnet/ Huonville – Franklin, Tas: Parklands - Camdale/ Somerset/ Wynyard ,Tas: Port Sorell, ACT: Belconnen South ,ACT: Gungahlin – South, ACT: Inner North Canberra – South, ACT: Inner South Canberra – North, ACT: Curtin/ Garran/ Hughes, ACT: Farrer/ Isaacs/ Mawson/ Pearce/ Torrens |

Note: The PHAs are shown once against their cut-off thresholds, i.e. PHAs in the 50% less threshold are cold for this threshold and above.

| Greater than the Australian Average | Population Health Areas (PHAs) |

| Four times | NT: Barkly/ Tennant Creek |

| Three and a half times | Qld: Carpentaria/ Mount Isa Region/ Northern Highlands, WA: Derby – West Kimberley/ Roebuck, WA: Halls Creek/ Kununurra, NT: Alice Springs – Remote |

| Two and half times | Qld: Kuranda/ Mareeba, SA: Coober Pedy/ Outback, NT: Alice Springs – Town |

| Two times | NSW: Bourke – Brewarrina/ Walgett – Lightning Ridge, Qld: Berserker/ Lakes Creek/ Rockhampton City, Qld: Far North, Qld: Bundaberg/ Bundaberg North/ Millbank area, SA: Renmark, WA: Broome, WA: South Hedland, NT: Elsey/ Gulf/ Victoria River, NT: Katherine |

| 90% | Qld: Babinda/ Innisfail/ Yarrabah, Qld: Johnstone/ Tully/ Wooroonooran, Qld: Charleville/ Far Central West/ Far South West, Qld: Kingaroy Region – North/ Nanango, WA: Carnarvon, WA: Roebourne, Tas: Mornington – Warrane |

| 80% | Qld: Logan Central/ Woodridge, Qld: Manoora/ Manunda/ Westcourt – Bungalow/ Woree, Qld: Barcaldine – Blackall/ Longreach, SA: Ceduna/ West Coast / Western, SA: Flinders Ranges/ Port Augusta |

| 70% | NSW: Cobar/ Coonamble/ Nyngan – Warren, Qld: Maryborough / Tinana, SA: Port Pirie, WA: Geraldton/ Geraldton – East, WA: Meekatharra, Tas: Acton – Upper Burnie/ Burnie – Wivenhoe, NT: Anindilyakwa/ East Arnhem/ Nhulunbuy |

| 60% | Qld: Kingston/ Slacks Creek, Qld: Caboolture, Qld: Daintree/ Port Douglas, Qld: Balonne/ Goondiwindi/ Inglewood - Waggamba/ Tara, Qld: Aroona/ Caloundra - Kings Beach/ Moffat Beach, SA: Barmera/ Berri, WA: Newman, Tas: Devonport |

| 50% | NSW: Moree Region/ Narrabri/ Narrabri Region, Vic: Bendigo, Qld: Zillmere, Qld: Atherton/ Herberton/ Malanda – Yungaburra, Qld: Central Highlands – Region, Qld: Banana/ Biloela, Qld: Bouldercombe/ Gracemere/ Mount Morgan, Qld: Emu Park/ Rockhampton Region - East/ Yeppoon, Qld: Labrador, Qld: Nambour, Qld: Charters Towers/ Dalrymple/ Ingham/ Palm Island, Qld: Burnett – North, SA: Elizabeth/ Smithfield - Elizabeth North, SA: Millicent |

Note: The PHAs are shown once against their cut-off thresholds, i.e. PHAs in the four times greater threshold are hot for this threshold and below.

| Greater than the Australian Average | Population Health Areas (PHAs) |

| 50% | Tas: West Ulverstone |

| 40% | NSW: Canada Bay – West, Tas: Legana/ Riverside/ Trevallyn, Tas: Burnie - Ulverstone Region, Tas: North West/ Waratah |

| 30% | NSW: Sydney - Haymarket - The Rocks, NSW: Burwood – Croydon, NSW: Ermington - Rydalmere/ Oatlands - Dundas Valley, NSW: Fairfield – East, NSW: Toongabbie - Constitution Hill, NSW: Engadine - Loftus/ Heathcote – Waterfall, NSW: Oyster Bay/ Sutherland area, Vic: Thornbury, Vic: Docklands/ Southbank/ West Melbourne, Vic: Albert Park, Vic: Bulleen/ Doncaster, Vic: Doncaster East, Vic: Templestowe/ Templestowe Lower, Vic: Hughesdale, Vic: Ballarat – North, Qld: St Lucia, SA: APY Lands, WA: Busselton Region, Tas: Newstead/ Norwood (Tas.)/ Youngtown – Relbia, Tas: Grindelwald - Lanena/ Hadspen – Carrick, Tas: Triabunna – Bicheno, ACT: Gungahlin - South |

| 20% | NSW: Erina - Green Point area, NSW: Baulkham Hills area, NSW: Castle Hill/ Glenhaven, NSW: Cherrybrook/ West Pennant Hills, NSW: Riverstone - Marsden Park, NSW: Glebe - Forest Lodge/ Pyrmont – Ultimo ,NSW: Bondi Junction area, NSW: Mortdale - Penshurst/ Peakhurst – Lugarno, NSW: South Hurstville - Blakehurst area, NSW: Riverwood, NSW: Kogarah - Rockdale – Coast, NSW: Canada Bay – East, NSW: Ashfield, NSW: Canterbury (North) - Ashbury area, NSW: Strathfield, NSW: Carlingford, NSW: North Rocks/ Northmead/ Winston Hills, NSW: Epping - North Epping/ Pennant Hills – Cheltenham, NSW: North Ryde - East Ryde/ Ryde – Putney, NSW: Cabramatta – Lansvale, NSW: Canley Vale - Canley Heights/ Fairfield, NSW: Fairfield - West area, NSW: Caringbah - Lilli Pilli, NSW: Cronulla - Miranda - Caringbah – West, NSW: Menai - Lucas Heights - Woronora area, NSW: Karabar/ Queanbeyan/ Queanbeyan – East, NSW: Cooma Region/ Jindabyne – Berridale, NSW: Kiama-Jamberoo-Gerringong ,NSW: St Georges Basin - Erowal Bay area, Vic: Brunswick West/ Pascoe Vale South ,Vic: Alphington - Fairfield/ Northcote, Vic: East Melbourne/ South Yarra – West ,Vic: Elwood, Vic: Richmond, Vic: Box Hill/ Box Hill North, Vic: Burwood/ Burwood East, Vic: Surrey Hills (East) - Mont Albert, Vic: Brighton / Brighton East, Vic: Murrumbeena, Vic: Kingston – Central, Vic: Bundoora – North, Vic: Gisborne/ Macedon/ Riddells Creek, Vic: Cairnlea, Vic: Delahey, Vic: Sydenham, Vic: Caroline Springs, Vic: Bendigo - Central East, Vic: Bannockburn/ Golden Plains - South/ Winchelsea, Vic: Lorne - Anglesea/ Torquay, Vic: Seymour Region, Vic: Yackandandah Qld: Centenary – West, Qld: Indooroopilly/ Taringa, WA: Canning – South, WA: Esperance Region, Tas: Hobart/ Lenah Valley - Mount Stuart/ West Hobart, Tas: Kings Meadows/ South Launceston/ Summerhill, Tas: Deloraine/ Westbury, Tas: Dilston - Lilydale/ Perth – Evandale, Tas: Bruny Island – Kettering, ACT: Ngunnawal/ Nicholls/ Palmerston, ACT: Farrer/ Isaacs/ Mawson/ Pearce/ Torrens |

Note: The PHAs are shown once against their cut-off thresholds, i.e. PHAs in the 50% less threshold are cold for this threshold and above.

| Greater than the Australian Average | Population Health Areas (PHAs) |

| Three and a half times | NT: Barkly/ Tennant Creek |

| Three times | NT: Alice Springs - Remote |

| Two times | NSW: Glendenning Dean Park/ Hassall Grove – Plumpton, Qld: Bundaberg/ Bundaberg North/ Millbank area, SA: Coober Pedy/ Outback, WA: South Hedland |

| 90% | NSW: Leeton/ Narrandera, Qld: Browns Plains/ Crestmead/ Marsden, Qld: Kuranda/ Mareeba, Qld: Charleville/ Far Central West/ Far South West, SA: Flinders Ranges/ Port Augusta, SA: Renmark, Tas: Acton - Upper Burnie/ Burnie – Wivenhoe, NT: Katherine |

| 80% | NSW: Bourke - Brewarrina/ Walgett - Lightning Ridge, NSW: Griffith Region, Vic: Broadmeadows, Vic: Cranbourne/ Cranbourne West, Vic: Bendigo, Qld: Caboolture, WA: Broome, NT: Daly - Tiwi - West Arnhem |

| 70% | NSW: Mount Druitt – Whalan, NSW: Cobar/ Coonamble/ Nyngan – Warren, NSW: Moree Region/ Narrabri/ Narrabri Region, NSW: Tamworth – West, Qld: Rocklea - Acacia Ridge, Qld: Kingston/ Slacks Creek, Qld: Far North (Qld) ,Qld: Kingaroy Region - North/ Nanango, SA: Elizabeth/ Smithfield - Elizabeth North, WA: Kalgoorlie, WA: Meekatharra |

| 60% | NSW: Mount Druitt - North West, NSW: Deniliquin, NSW: Maryland - Fletcher – Minmi, Vic: Roxburgh Park – Somerton, Vic: Frankston, Qld: Inala - Richlands/ Wacol, Qld: Ipswich - Central/ North Ipswich – Tivoli, Qld: New Chum/ Redbank Plains, Qld: Bethania - Waterford/ Loganlea/ Waterford West, Qld: Logan Central/ Woodridge, Qld: Burpengary, Qld: Babinda/ Innisfail/ Yarrabah, Qld: Berserker/ Lakes Creek/ Rockhampton City, Qld: Maryborough (Qld)/ Tinana, SA: Davoren Park, SA: Ceduna/ West Coast (SA)/ Western, SA: Millicent, WA: Boulder/ Kambalda - Coolgardie – Norseman |

| 50% | NSW: Prospect Reservoir/ Rooty Hill – Minchinbury, NSW: Erskine Park/ St Clair, NSW: Homebush Bay – Silverwater, NSW: Broken Hill/ Far West, NSW: Seaham – Woodville, NSW: Muswellbrook, NSW: Kempsey, NSW: Cootamundra/ Gundagai/ Junee/ Temora, Vic: Heidelberg West, Vic: Hampton Park – Lynbrook, Vic: Dandenong, Vic: Laverton, Vic: Werribee, Vic: Corio – Norlane, Qld: Chermside, Qld: Esk/ Lake Manchester - England Creek/ Lowood, Qld: Beenleigh/ Eagleby, Qld: Barcaldine - Blackall/ Longreach, Qld: Aroona/ Caloundra - Kings Beach/ Moffat Beach, Qld: Burnett – North, SA: Christie Downs/ Hackham West - Huntfield Heights, WA: Katanning, NT: Darwin - Nightcliff area , NT: Darwin - Marrara/ Berrimah area |

Note: The PHAs are shown once against their cut-off thresholds, i.e. PHAs in the four times greater threshold are hot for this threshold and below.

| Less than the Australian Average | Population Health Areas (PHAs) |

| 50% | Qld: St Lucia Tas: Bruny Island - Kettering Tas: West Ulverstone |

| 40% | NSW: Erina - Green Point area, NSW: Sydney - Haymarket - The Rocks, NSW: Bondi Junction area, NSW: Cremorne - Cammeray/ Neutral Bay – Kirribilli, NSW: Blackheath - Megalong Valley/ Katoomba – Leura, NSW: Cobbitty – Leppington, NSW: Kiama-Jamberoo-Gerringong, Vic: Docklands/ Southbank/ West Melbourne, Vic: Ballarat – North, Qld: Chapel Hill/ Fig Tree Pocket/ Kenmore, SA: North Adelaide, SA: Aldgate - Stirling/ Uraidla – Summertown, SA: Burnside - Wattle Park, SA: Glenside - Beaumont/ Toorak Gardens, SA: Naracoorte Region, WA: Busselton Region, WA: Esperance Region, Tas: Kingston Beach/ Taroona area, Tas: Miandetta - Don/ Turners Beach – Forth |

| 30% | NSW: Baulkham Hills area, NSW: Castle Hill/ Glenhaven, NSW: Cherrybrook/ West Pennant Hills, NSW: Sydney Inner City - North East, NSW: Double Bay area, NSW: Dover Heights/ Rose Bay - Vaucluse - Watsons Bay, NSW: Mortdale - Penshurst/ Peakhurst – Lugarno, NSW: South Hurstville - Blakehurst area, NSW: Riverwood, NSW: Canada Bay – West, NSW: Canada Bay – East, NSW: Burwood – Croydon, NSW: Canterbury (North) - Ashbury area , NSW: Strathfield, NSW: Lane Cove - Greenwich/ St Leonards – Naremburn, NSW: Willoughby - Castle Cove – Northbridge, NSW: St Ives/ Turramurra/ Wahroonga – Warrawee, NSW: North Sydney - Mosman – West, NSW: Mosman, NSW: Bayview - Elanora Heights/ Warriewood - Mona Vale, NSW: Blue Mountains - North Region, NSW: Carlingford, NSW: Epping - North Epping/ Pennant Hills – Cheltenham, NSW: Ryde - Hunters Hill – South, Vic: Armadale/ Toorak, Vic: Kew/ Kew East, Vic: Ivanhoe East – Eaglemont, Vic: Strathmore, Vic: Gisborne/ Macedon/ Riddells Creek, Vic: Yackandandah, Qld: Auchenflower/ Toowong, Qld: Samford Valley, SA: Norwood (SA)/ St Peters – Marden, SA: Belair/ Bellevue Heights/ Blackwood, WA: City Beach/ Floreat, WA: Cottesloe - Claremont – South, WA: Cottesloe - Claremont – Central, WA: Duncraig/ Hillarys/ Sorrento – Marmion, WA: Joondalup - North Coast, WA: Stirling – West, WA: Applecross - Ardross/ Bateman/ Booragoon, WA: Bull Creek/ Leeming/ Murdoch – Kardinya, Tas: Hobart/ Lenah Valley - Mount Stuart/ West Hobart, Tas: Mount Nelson/ Sandy Bay/ South Hobart area, Tas: Legana/ Riverside/ Trevallyn, Tas: Prospect Vale – Blackstone, Tas: Triabunna – Bicheno, Tas: Burnie - Ulverstone Region, Tas: North West/ Waratah |

| 20% | NSW: Gosford - South East, NSW: Dural - Wisemans Ferry, NSW: Riverstone - Marsden Park, NSW: Marrickville, NSW: Glebe - Forest Lodge/ Pyrmont – Ultimo, NSW: Kingsgrove (North) – Earlwood, NSW: Hurstville/ Narwee - Beverly Hills, NSW: Kogarah - Rockdale – Coast, NSW: Balmain/ Lilyfield – Rozelle, NSW: Leichhardt – Annandale, NSW: Ashfield, NSW: Dulwich Hill - Lewisham/ Haberfield - Summer Hill, NSW: Chatswood area, NSW: Hornsby – Waitara, NSW: Normanhurst - Thornleigh – Westleigh, NSW: Manly, NSW: Avalon - Palm Beach/ Newport – Bilgola, NSW: Cromer/ Narrabeen – Collaroy, NSW: Bargo/ Picton - Tahmoor – Buxton, NSW: Blaxland - Warrimoo – Lapstone, NSW: Ermington - Rydalmere/ Oatlands - Dundas Valley, NSW: Fairfield – East, NSW: Macquarie Park – Marsfield, NSW: North Ryde - East Ryde/ Ryde – Putney, NSW: Cabramatta – Lansvale, NSW: Canley Vale - Canley Heights/ Fairfield, NSW: Cronulla - Miranda - Caringbah – West, NSW: Oyster Bay/ Sutherland area, NSW: Anna Bay/ Nelson Bay Peninsula, NSW: Balgownie - Fairy Meadow, NSW: Adamstown – Kotara, NSW: Stockton - Fullerton Cove, NSW: Bowral/ Robertson - Fitzroy Falls, NSW: Mittagong, Vic: Essendon - Aberfeldie/ Moonee Ponds, Vic: Albert Park, Vic: Carlton North - Princes Hill/ Fitzroy North, Vic: Camberwell/ Surrey Hills (West) – Canterbury, Vic: Hawthorn/ Hawthorn East, Vic: Bulleen/ Doncaster, Vic: Doncaster East, Vic: Templestowe/ Templestowe Lower, Vic: Beaumaris/ Sandringham - Black Rock, Vic: Hurstbridge/ Panton Hill/ Research, Vic: Niddrie - Essendon West, Vic: Maribyrnong, Vic: Woodend, Vic: Lorne - Anglesea/ Torquay, Vic: Ocean Grove - Barwon Heads/ Queenscliff, Vic: Ararat Region, Vic: Irymple/ Mildura Region, Qld: Centenary – East, Qld: Centenary – West, Qld: Kenmore - Brookfield - Moggill – West, Qld: Indooroopilly/ Taringa, Qld: The Gap/ Upper Kedron - Ferny Grove, Qld: Ashgrove/ Bardon, Qld: Highfields, Qld: Middle Ridge/ Rangeville/ Toowoomba – East, SA: Adelaide, SA: Goodwood – Millswood, SA: Highbury – Dernancourt, SA: Colonel Light Gardens/ Mitcham (SA), SA: Clarendon/ McLaren Vale/ Willunga, SA: Loxton/ Loxton Region/ Renmark Region, WA: Halls Head – Erskine, WA: Perth City – West, WA: Glen Forrest - Darlington/ Helena Valley area, WA: Kingsley/ Padbury/ Woodvale, WA: Dianella/ Yokine - Coolbinia – Menora, WA: Mindarie - Quinns Rocks – Jindalee, WA: Armadale – West, WA: Canning – South, WA: Kalamunda – East, WA: Como/ South Perth – Kensington, WA: Bicton - Palmyra/ Melville/ Winthrop, WA: Australind – Leschenault, WA: Albany - South-East or Albany – Region, Tas: Beauty Point – Beaconsfield, Tas: Grindelwald - Lanena/ Hadspen – Carrick, Tas: Cygnet/ Huonville – Franklin, Tas: Parklands - Camdale/ Somerset/ Wynyard, Tas: Port Sorell, ACT: Gungahlin – South, ACT: Inner North Canberra – South, ACT: Weston Creek, ACT: Curtin/ Garran/ Hughes, ACT: Farrer/ Isaacs/ Mawson/ Pearce/ Torrens |

Note:The PHAs are shown once against their cut-off thresholds, i.e. PHAs in the 50% less threshold are cold for this threshold and above.

| Greater than the Australian Average | Population Health Areas (PHAs) |

| Four times | Qld: New Chum/ Redbank Plains, SA: Coober Pedy/ Outback, WA: Leinster – Leonora, WA: Derby - West Kimberley/ Roebuck, WA: Halls Creek/ Kununurra, NT: Alice Springs – Town, NT: Alice Springs – Remote, NT: Barkly/ Tennant Creek, NT: Daly - Tiwi - West Arnhem, NT: Anindilyakwa/ East Arnhem/ Nhulunbuy, NT: Elsey/ Gulf/ Victoria River |

| Three and a half times | Qld: Inala - Richlands/ Wacol, NT: Katherine |

| Three times | Vic: Laverton, Qld: Darra - Sumner/ Durack/ Oxley, WA: Broome |

| Two and a half times | Vic: Noble Park, Qld: Far North, SA: APY Lands, WA: South Hedland, NT: Driver/ Gray/ Moulden/ Woodroffe |

| Two times | NSW: Bankstown, NSW: Fairfield – South, NSW: Bossley Park - Abbotsbury area, Vic: Flemington, Vic: North Melbourne, Vic: Dandenong, Vic: Springvale/ Springvale South, Vic: St Albans – North/ Kings Park, Qld: Rocklea - Acacia Ridge, Qld: Bundamba/ Riverview, Qld: Churchill - Yamanto/ Raceview/ Ripley, Qld: Browns Plains/ Crestmead/ Marsden ,Qld: Kingston/ Slacks Creek, Qld: Logan Central/ Woodridge, NT: Darwin - Marrara/ Berrimah area |

| 90% | NSW: Sydney Inner City - South West, NSW: Fairfield - West area, Vic: Collingwood/ Fitzroy, Vic: Lalor/ Thomastown, Vic: Broadmeadows, Vic: Cairnlea, Qld: Springfield - Redbank – North, SA: Charles Sturt - North West, NT: Darwin – Inner, NT: Darwin - Nightcliff area |

| 80% | NSW: Greenacre - Mount Lewis/ Yagoona – Birrong, NSW: Auburn, Vic: Meadow Heights, Vic: Keysborough, Vic: Ardeer - Albion/ Sunshine/ Sunshine West, Qld: Carpentaria/ Mount Isa Region/ Northern Highlands, SA: Dry Creek - South/ Port Adelaide/ The Parks |

| 70% | NSW: North Parramatta, NSW: Hoxton Park - Horningsea Park, Vic: Richmond, Vic: Doveton, Vic: Braybrook, SA: Davoren Park, SA: Elizabeth/ Smithfield - Elizabeth North, SA: Christie Downs/ Hackham West - Huntfield Heights, WA: Balga - Mirrabooka/ Nollamara – Westminster, WA: Kalgoorlie, WA: Newman |

| 60% | NSW: Glendenning Dean Park/ Hassall Grove – Plumpton, NSW: Homebush Bay – Silverwater, NSW: Lidcombe - Regents Park/ Rookwood Cemetery, NSW: Guildford West/ Merrylands - Holroyd area, NSW: Girraween - Westmead/ Parramatta – Rosehill, NSW: Casula/ Prestons – Lurnea, Vic: Footscray/ West Footscray – Tottenham, Qld: Chambers Flat/ Munruben - Park Ridge South, WA: Meekatharra |

| 50% | NSW: Mount Druitt - North West, NSW: Sydney Inner City - North East, NSW: Bass Hill - Georges Hall/ Condell Park, NSW: Granville - Clyde/ Guildford - South Granville, NSW: Cabramatta – Lansvale, NSW: Canley Vale - Canley Heights/ , Fairfield, Vic: Preston, Qld: Moorooka/ Salisbury – Nathan, Qld: Sunnybank/ Sunnybank Hills, Qld: Ipswich – East, Qld: Beenleigh/ Eagleby, Qld: Bethania - Waterford/ Loganlea/ Waterford West, Qld: Manoora/ Manunda/ Westcourt - Bungalow/ Woree, Qld: Babinda/ Innisfail/ Yarrabah, SA: Enfield - Blair Athol, SA: Flinders Ranges/ Port Augusta |

Note: The PHAs are shown once against their cut-off thresholds, i.e. PHAs in the four times greater threshold are hot for this threshold and below.

| Less than the Australian Average | Population Health Areas (PHAs) |

| 50% | NSW: Gosford - South East, NSW: Erina - Green Point area, NSW: Wyong – East, NSW: Wyong, NSW: Bayview - Elanora Heights/ Warriewood - Mona Vale, NSW: Yass Region, NSW: Merimbula - Tura Beach, NSW: Cowra, NSW: Parkes (NSW)/ Parkes Region, NSW: Laurieton - Bonny Hills, NSW: Port Macquarie – East, NSW: Port Macquarie – West, NSW: Port Macquarie Region/ Wauchope, NSW: Albury – East, NSW: Deniliquin Region/ Moama, Vic: Mount Eliza, Vic: Ballarat – North, Vic: Bacchus Marsh Region/ Gordon (Vic.), Vic: Bendigo - Central East, Vic: Strathfieldsaye, Vic: Bendigo Region – South, Vic: Myrtleford, Vic: Horsham Region, Vic: Irymple/ Mildura Region, Vic: Merbein, Vic: Cobram/ Numurkah, Vic: Moira/ Yarrawonga, Qld: Broadsound - Nebo/ Clermont/ Moranbah, Qld: Pioneer Valley/ Seaforth – Calen, Qld: Branyan - Kensington/ Bundaberg Region – North, SA: Kimba - Cleve - Franklin Harbour, SA: Roxby Downs, SA: Naracoorte Region, SA: Loxton/ Loxton Region/ Renmark Region, WA: City Beach/ Floreat, WA: Glen Forrest - Darlington/ Helena Valley area, WA: Armadale – West, WA: Busselton Region, WA: Capel, WA: Dardanup/ Eaton - Pelican Point, WA: Manjimup/ Pemberton, WA: Esperance Region, WA: Geraldton – South, WA: Albany - South-East or Albany – Region, Tas: Newstead/ Norwood (Tas.)/ Youngtown – Relbia, Tas: Legana/ Riverside/ Trevallyn, Tas: Prospect Vale – Blackstone, Tas: Dilston - Lilydale/ Perth – Evandale, Tas: West Ulverstone, Tas: Miandetta - Don/ Turners Beach – Forth, Tas: Port Sorell, Tas: West Coast / Wilderness – West, ACT: Cotter – Namadgi |

| 40% | NSW: Kariong/ Point Clare – Koolewong, NSW: Terrigal - North Avoca area, NSW: Wyong - North East, NSW: Warnervale - Wadalba area, NSW: Manly, NSW: Blackheath - Megalong Valley/ Katoomba – Leura, NSW: Cooma, NSW: South Coast – North, NSW: Lithgow area, NSW: Mudgee/ Mudgee Region – West, NSW: Coonabarabran/ Gilgandra/ Narromine, NSW: Dubbo Region, NSW: Singleton, NSW: Tea Gardens - Hawks Nest, NSW: Kiama-Jamberoo-Gerringong, NSW: Gunnedah/ Gunnedah Region, NSW: Quirindi, NSW: Ballina Region/ Bangalow, NSW: Leeton/ Narrandera, NSW: Huskisson/ Tomerong area, Vic: Camberwell/ Surrey Hills (West) – Canterbury, Vic: Hawthorn/ Hawthorn East, Vic: Beaumaris/ Sandringham - Black Rock, Vic: Strathmore, Vic: Gisborne/ Macedon/ Riddells Creek, Vic: Monbulk - Silvan/ Mount Evelyn, Vic: Frankston South, Vic: Flinders/ Mount Martha, Vic: Kangaroo Flat - Golden Square, Vic: Maiden Gully, Vic: Castlemaine/ Castlemaine Region, Vic: Bendigo Region – North, Vic: Loddon, Vic: Highton/ Newtown (Vic.), Vic: Leopold, Vic: Lorne - Anglesea/ Torquay, Vic: Alexandra/ Euroa/ Nagambie/ Upper Yarra Valley, Vic: Seymour Region, Vic: Benalla Region/ Wangaratta Region, Vic: Yackandandah, Vic: Drouin, Vic: Alps - East/ Bruthen - Omeo/ Orbost/ Paynesville, Vic: Echuca/ Lockington – Gunbower, Vic: Kyabram/ Rochester/ Rushworth, Vic: Colac Region/ Otway, Qld: Eimeo - Rural View/ Mount Pleasant - Glenella area, Qld: Ooralea - Bakers Creek/ Walkerston – Eton, Qld: Kingaroy/ Kingaroy Region – South, SA: Aldgate - Stirling/ Uraidla – Summertown, SA: Strathalbyn Region, WA: Currambine – Kinross, WA: Duncraig/ Hillarys/ Sorrento – Marmion, WA: Greenwood – Warwick, WA: Innaloo - Doubleview/ Karrinyup - Gwelup – Carine, WA: Stirling – West, WA: Kalamunda – East, WA: Coogee/ North Coogee, WA: Applecross - Ardross/ , Bateman/ Booragoon, WA: Bull Creek/ Leeming/ Murdoch – Kardinya, WA: Baldivis/ Singleton - Golden Bay - Secret Harbour, WA: Augusta/ Margaret River, WA: Australind – Leschenault, WA: Gelorup - Dalyellup – Stratham ,WA: Bridgetown - Boyup Brook/ Donnybrook – Balingup, WA: Denmark/ Plantagenet, WA: Cunderdin/ Merredin/ Mukinbudin, Tas: Kingston - Huntingfield/ Margate – Snug, Tas: Longford/ Northern Midlands, Tas: Bruny Island – Kettering, Tas: Burnie - Ulverstone Region, Tas: Parklands - Camdale/ Somerset/ Wynyard, Tas: King Island, Tas: North West/ Waratah |

| 30% | NSW: Umina - Booker Bay - Patonga/ Woy Woy – Blackwall, NSW: Bateau Bay - Killarney Vale/ The Entrance, NSW: Chittaway Bay - Tumbi Umbi/ Tuggerah - Kangy Angy, NSW: Gorokan - Kanwal – Charmhaven, NSW: Bondi Junction area, NSW: Asquith - Mount Colah/ Berowra - Brooklyn – Cowan, NSW: Cremorne - Cammeray/ Neutral Bay – Kirribilli, NSW: Avalon - Palm Beach/ Newport – Bilgola, NSW: Cromer/ Narrabeen – Collaroy, NSW: Bargo/ Picton - Tahmoor – Buxton, NSW: Douglas Park - Appin/ The Oaks – Oakdale, NSW: Blaxland - Warrimoo – Lapstone, NSW: Blue Mountains - North Region, NSW: Oyster Bay/ Sutherland area, NSW: Goulburn Region, NSW: Yass, NSW: Braidwood, NSW: Karabar/ Queanbeyan/ Queanbeyan – East, NSW: Cooma Region/ Jindabyne – Berridale, NSW: South Coast - Batemans Bay, NSW: Bega - Tathra/ Bega-Eden Hinterland, NSW: Bathurst/ Bathurst – East, NSW: Blayney, NSW: Woolgoolga – Arrawarra, NSW: Cessnock Region, NSW: Muswellbrook, NSW: Muswellbrook Region, NSW: Forster/ Tuncurry, NSW: Macksville - Scotts Head/ Nambucca Heads, NSW: Albury - North/ Lavington, NSW: Corowa/ Corowa Region/ Tocumwal, NSW: Inverell Region – West, NSW: Griffith (NSW), NSW: St Georges Basin - Erowal Bay area, NSW: Ulladulla, NSW: Mittagong ,Vic: Docklands/ Southbank/ West Melbourne, Vic: East Melbourne/ South Yarra – West, Vic: Parkville, Vic: Armadale/ Toorak, Vic: Hughesdale, Vic: Greensborough/ Montmorency - Briar Hill, Vic: Plenty - Yarrambat/ Wattle Glen - Diamond Creek, Vic: Bundoora – North, Vic: Sunbury/ Sunbury – South, Vic: Yarra Ranges - South West, Vic: Beaconsfield - Officer/ Emerald – Cockatoo, Vic: Dromana, Vic: Golden Plains – North, Vic: California Gully – Eaglehawk, Vic: Woodend, Vic: Bannockburn/ Golden Plains - South/ Winchelsea, Vic: Lara, Vic: Kilmore - Broadford/ Yea, Vic: Wangaratta, Vic: Beechworth/ Chiltern - Indigo Valley, Vic: Bright - Mount Beauty/ Towong, Vic: West Wodonga/ Wodonga, Vic: Bairnsdale/ Lake King/ Lakes Entrance, Vic: Foster/ Korumburra/ Leongatha/ Wilsons Promontory, Vic: Churchill, Vic: Traralgon/ Yallourn North – Glengarry, Vic: Ararat Region, Vic: Buloke/ Gannawarra/ Kerang, Vic: Shepparton Region – East, Qld: The Gap/ Upper Kedron - Ferny Grove, Qld: Earlville - Bayview Heights/ Kanimbla – Mooroobool, Qld: East Mackay/ Mackay/ South Mackay/ West Mackay, Qld: Peregian/ Sunshine Beach, Qld: Northern Beaches/ Townsville – South, Qld: Burrum - Fraser/ Maryborough Region – South, SA: Clarendon/ McLaren Vale/ Willunga ,SA: Fulham/ West Beach, SA: Kadina/ Moonta, SA: Grant, WA: Dawesville - Bouvard/ Falcon – Wannanup ,WA: Mandurah – North, WA: Cottesloe - Claremont – South, WA: Cottesloe - Claremont – Central, WA: Hazelmere - South Guildford, WA: Heathridge - Connolly/ Joondalup – Edgewater, WA: Joondalup - North Coast, WA: Carramar/ Tapping - Ashby – Sinagra, WA: Byford/ Mundijong/ Serpentine – Jarrahdale, WA: Collie, WA: Esperance, WA: Exmouth, WA: Gnowangerup/ Kojonup, WA: Kulin/ Murray/ Wagin, Tas: Bridgewater – Gagebrook, Tas: Cambridge/ South Arm, Tas: Beauty Point – Beaconsfield, Tas: Grindelwald - Lanena/ Hadspen – Carrick, Tas: George Town/ Scottsdale/ St Helens, Tas: Central Highlands (Tas.), ACT: Belconnen North, ACT: Gungahlin – North, ACT: Inner South Canberra – North |

| 20% | NSW: Gosford - Springfield/ Wyoming, NSW: North Sydney - Mosman – West, NSW: Mosman ,NSW: Dee Why - North Curl Curl area, NSW: Warringah – South, NSW: Caringbah - Lilli Pilli, NSW: Cronulla - Miranda - Caringbah – West, NSW: Engadine - Loftus/ Heathcote – Waterfall, NSW: Menai - Lucas Heights - Woronora area, NSW: Queanbeyan West and Region, NSW: Bathurst Region, NSW: Oberon, NSW: Cowra Region/ Grenfell/ West Wyalong, NSW: Maclean - Yamba – Iluka, NSW: Korora - Emerald Beach area, NSW: Cobar/ Coonamble/ Nyngan – Warren, NSW: Dubbo – South, NSW: Branxton - Greta - Pokolbin/ Singleton Region, NSW: Maitland – North, NSW: Anna Bay/ Nelson Bay Peninsula NSW: Raymond Terrace, NSW: Shellharbour – Flinders, NSW: Balgownie - Fairy Meadow, NSW: Kempsey Region/ Nambucca Heads Region, NSW: Taree/ Wingham, NSW: Albury - South/ Albury Region, NSW: Inverell/ Inverell Region – East, NSW: Moree, NSW: Tamworth – North, NSW: Tamworth Region, NSW: Wangi Wangi – Rathmines, NSW: Ballina, NSW: Lismore Region, NSW: Tumbarumba/ Tumut Region, NSW: Tumut, NSW: Berry - Kangaroo Valley, NSW: Callala Bay - Currarong/ Culburra Beach, NSW: Bowral/ Robertson - Fitzroy Falls, NSW: Hill Top - Colo Vale/ Southern Highlands, NSW: Moss Vale – Berrima, Vic: Ashburton (Vic.), Vic: Glen Iris – East, Vic: Surrey Hills (East) - Mont Albert, Vic: Brighton (Vic.)/ Brighton East, Vic: Kingston – Central, Vic: Eltham, Vic: Wallan/ Whittlesea, Vic: Keilor, Vic: Donvale - Park Orchards/ Warrandyte - Wonga Park, Vic: Healesville - Yarra Glen, Vic: Sydenham, Vic: Bacchus Marsh, Vic: Ballarat - South/ Delacombe, Vic: Avoca/ Beaufort/ Maryborough Region, Vic: Kyneton, Vic: Geelong West - Hamlyn Heights, Vic: Clifton Springs, Vic: Ocean Grove - Barwon Heads/ Queenscliff, Vic: Mount Baw Baw Region/ Trafalgar (Vic.)/ Warragul, Vic: Wonthaggi – Inverloch, Vic: Alps - West/ Maffra/ Rosedale, Vic: Horsham, Vic: Mooroopna/ Shepparton – South, Qld: Wellington Point, Qld: Kenmore - Brookfield - Moggill – West, Qld: Chapel Hill/ Fig Tree Pocket/ Kenmore, Qld: St Lucia, Qld: Scarborough – Newport, Qld: Samford Valley, Qld: Lawnton/ Petrie, Qld: Cairns - North – Coast, Qld: Crows Nest - Rosalie/ Jondaryan, Qld: Clifton - Greenmount/ Southern Downs, Qld: Rockhampton – North, Qld: Rockhampton – Central, Qld: Broadbeach Waters/ Mermaid Beach – Broadbeach, Qld: Guanaba - Springbrook/ Tamborine – Canungra, Qld: Andergrove - Beaconsfield/ North Mackay area, Qld: Middle Ridge/ Rangeville/ Toowoomba – East, Qld: Burnett – North, SA: North Adelaide, SA: Mount Barker, SA: Wakefield - Barunga West, SA: Peterborough - Mount Remarkable, WA: Halls Head – Erskine, WA: Pinjarra, WA: Mount Hawthorn - Leederville/ North Perth, WA: Perth City – West, WA: Ellenbrook/ Gidgegannup/ The Vines, WA: Butler - Merriwa - Ridgewood/ Clarkson, WA: Mindarie - Quinns Rocks – Jindalee, WA: Yanchep, WA: Forrestdale - Harrisdale - Piara Waters, WA: Parkwood - Ferndale – Lynwood, WA: Port Kennedy, WA: Busselton, WA: College Grove - Carey Park/ Davenport, WA: Harvey/ Waroona, WA: Chittering/ Gingin – Dandaragan, WA: Dowerin/ Moora/ Toodyay, WA: Northam/ York – Beverley, Tas: New Norfolk, Tas: Invermay/ Mowbray/ Newnham/ Ravenswood/ Waverley, Tas: Triabunna – Bicheno, Tas: Devonport |

Note: The PHAs are shown once against their cut-off thresholds, i.e. PHAs in the 50% less threshold are cold for this threshold and above.

Background

Preventing unnecessary hospital admissions continues to be a major objective of healthcare reform internationally (WHO 2016) and in Australia (Falster and Jorm 2017). This objective is reflected in a current Australian Government Department of Health initiative, ‘Keeping Australians out of hospital’ (Department of Health 2019). This initiative will fund research to reduce avoidable hospitalisations and improve the prevention and management of chronic and complex health conditions. One possible way to minimise hospitalisations is to provide timely and effective primary health care to patients before they become so unwell that they need hospital care. Information as to the degree of timely and accessible, quality primary and community-based care is available in the form of an indirect proxy indicator, the rate of Potentially Preventable Hospitalisations.

Potentially Preventable Hospitalisations (PPHs) are hospitalisations for a condition where an admission to hospital could have potentially been prevented through the provision of appropriate individualised preventative health intervention and early disease management usually delivered in primary care and community-based care settings (AIHW 2018a). The current national standard for PPHs was agreed to in 2015 and was adopted in reporting data from 2012-13 onwards (NHPA 2015; 2017). In Australia, the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW 2018b) report that there were an estimated 27.3 PPHs per 1,000 population in 2016-2017 accounting for 6.5% of all hospital separations – 8.4% of public hospital separations and 3.6% of private hospital separations. Additionally, more than three quarters of all PPHs (77%) were treated in public hospitals. A study into hospitalisations in regional Queensland found that the two-year costs for PPH were $32.7million, which was 10.7% of the estimated total health care expenditure for hospital separations (Harriss et al. 2018).

Definitions

A PPH is identified using 22 ICD-10-AM diagnosis codes recorded in the Australian hospital morbidity system that have been assigned to patients admitted to a public acute or to a private hospital. Table 9 lists the conditions under the three PPH classifications of Acute conditions, Chronic conditions and Vaccine-preventable conditions. The rates of hospitalisation for these conditions in 2016-2017 were 13.0, 12.5 and 2.1 per 1,000 population, respectively. These rates represent an increase of 2.6%, 3.7% and 7.4% since 2015-2016 (AIHW 2018b)

| Acute conditions | Chronic conditions | Vaccine-preventable conditions |

| Urinary Tract Infections (UTI) | Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD) | Pneumonia and Influenza (vaccine-preventable) |

| Dental Conditions | Congestive Cardiac Failure (CCF) | Other vaccine-preventable conditions |

| Cellulitis | Iron Deficiency Anaemia | - |

| Ear, Nose and Throat Infections (ENT) | Diabetes complications | - |

| Convulsions and Epilepsy | Angina | - |

| Gangrene | Asthma | - |

| Perforated or Bleeding Ulcer | Hypertension | - |

| Pelvic Inflammatory Disease (PID) | Bronchiectasis | - |

| Eclampsia | Rheumatic Heart Disease | - |

| Pneumonia and Influenza (non-Vaccine-Preventable) | Nutritional Deficiencies | - |

Significance to health policy

The PPH indicator(s) are officially used as a national accessibility and effectiveness health performance progress measure within the Australian National Healthcare Agreement corresponding to the outcome, 'Australians receive appropriate high quality and affordable primary and community health services' (AIHW 2018b). It is also a formal indicator within the National Health Performance and Accountability Framework (Falster and Jorm 2017). The measure is therefore tied directly to hospital funding (Passey et al. 2015).

The indicator(s) are seen by policy makers as an opportunity to undertake reform and drive innovation to improve health service delivery and clinical practice in the primary care setting. For example, analysis of PPH variation in Queensland has led the Queensland Clinical Senate to recommend that PPH data be shared with local healthcare service clinicians and their provider organisations (such as Primary Health Networks) (AIHW 2018c). Routine regional reporting has also been called for to help monitor performance and evaluate policy and program initiatives (Banham et al. 2010).

Interpretation of the measure

Potentially Preventable Hospitalisations have been researched for over 30 years and over this time the terminology and definitions have changed internationally (Purdy et al. 2009) and in Australia. Past literature reviews of the evidence base have shown that hospitalisations which have been also been defined as unplanned admissions or avoidable or ambulatory care sensitive conditions (Ansari 2007; Rosano et al. 2012) have an inverse relationship with accessibility to primary care. A focus on the literature involving chronic conditions has also reported similar conclusions (van Loenen et al. 2014; Gibson et al. 2013; Wolters et al. 2017). For the majority of PPH conditions, these literature reviews provide strong evidence of the inverse relationship between accessibility to primary care and PPH rates. It must be noted however, that the applicability of outcomes to the Australian setting was limited by the inclusion of very few Australian studies and/or a high representation of US-based studies (Erny-Albrecht et al. 2016). Interestingly for dental conditions in Australia, an empirical study found a reverse relationship with high rates of hospital admission associated with higher dentists per capita (Yap et al. 2018).

The indicator(s) represent a supply-based measure, calculated as a rate of admission to hospital for the conditions highlighted in Table 9. A high rate of PPHs may indicate an increased prevalence of the conditions in the community, poorer functioning of the non-hospital care system or an appropriate use of the hospital system to respond to greater need (AIHW 2018b).

There are three broad categories of PPHs provided by the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare which have different interpretations of preventability (AIHW 2018b):

- Acute - conditions that may not be preventable, but theoretically would not result in hospitalisation if adequate and timely care (usually non-hospital) was received. These include eclampsia, pneumonia (not vaccine-preventable), pyelonephritis, perforated ulcer, cellulitis, urinary tract infections, pelvic inflammatory disease, ear, nose and throat infections, and dental conditions. These conditions make up around 41% of all PPH admissions (NHPA 2015)

- Chronic - conditions that may be preventable through behaviour modification and lifestyle change, but can also be managed effectively through timely care (usually non-hospital) to prevent deterioration and hospitalisation. These conditions include diabetes complications, asthma, angina, hypertension, congestive heart failure, nutritional deficiencies and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. These conditions make up around 56% of PPH admissions (NHPA 2015).

- Vaccine preventable - diseases that can be prevented by proper vaccination, including influenza, bacterial pneumonia, hepatitis, tetanus, diphtheria, pertussis (whooping cough), chicken pox, measles, mumps, rubella, polio and haemophilus meningitis. The conditions are considered to be preventable, rather than the hospitalisation. These conditions make up around 4% of PPH admissions (NHPA 2015).

It is important to note that many acute PPH admissions often reflect patients with underlying chronic conditions, for example, Harriss et al. (2018) found that up to 76.5% of all PPHs in their regional Queensland hospital study had underlying chronic conditions.

Falster and Jorm 2017 report that the indicator rate can be presented in three ways; a comparison between geographic regions, a breakdown by condition and population subgroup, and a temporal trend in PPH rates. For example, in reviewing Australia’s health in 2018 (AIHW 2018d), PPH rates are compared by remoteness area of residence (across capital cities, regional and remote areas), socioeconomic status of area of residence, country of birth of patient and Indigenous status.

At the state level, rates were stable across the three PPH classifications except for the Northern Territory (with twice the national rate) and Queensland (with a rate 21.5% above the national rate (AIHW 2018b). Rates of Indigenous Australians were almost three (2.9) times those for non-Indigenous Australians.

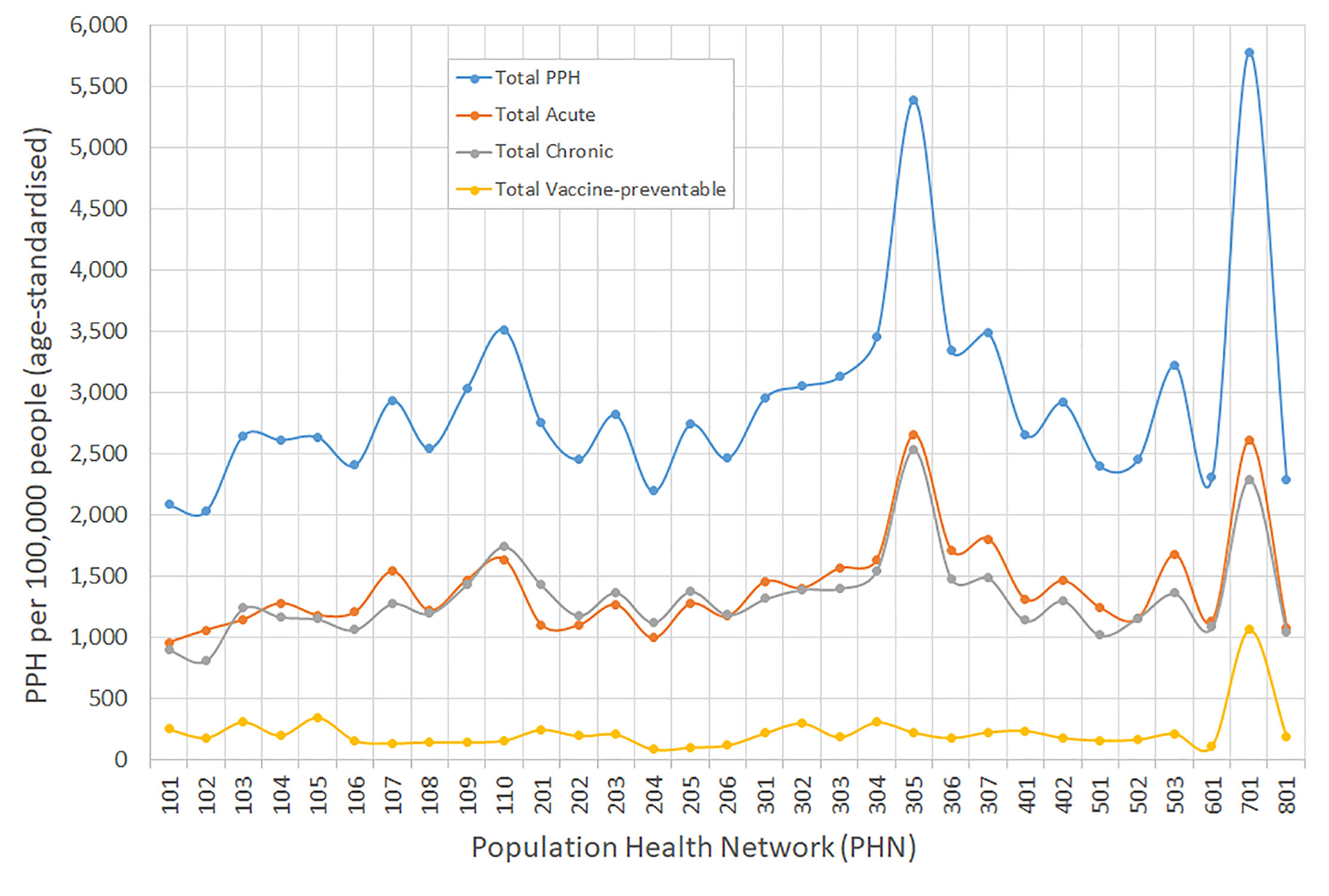

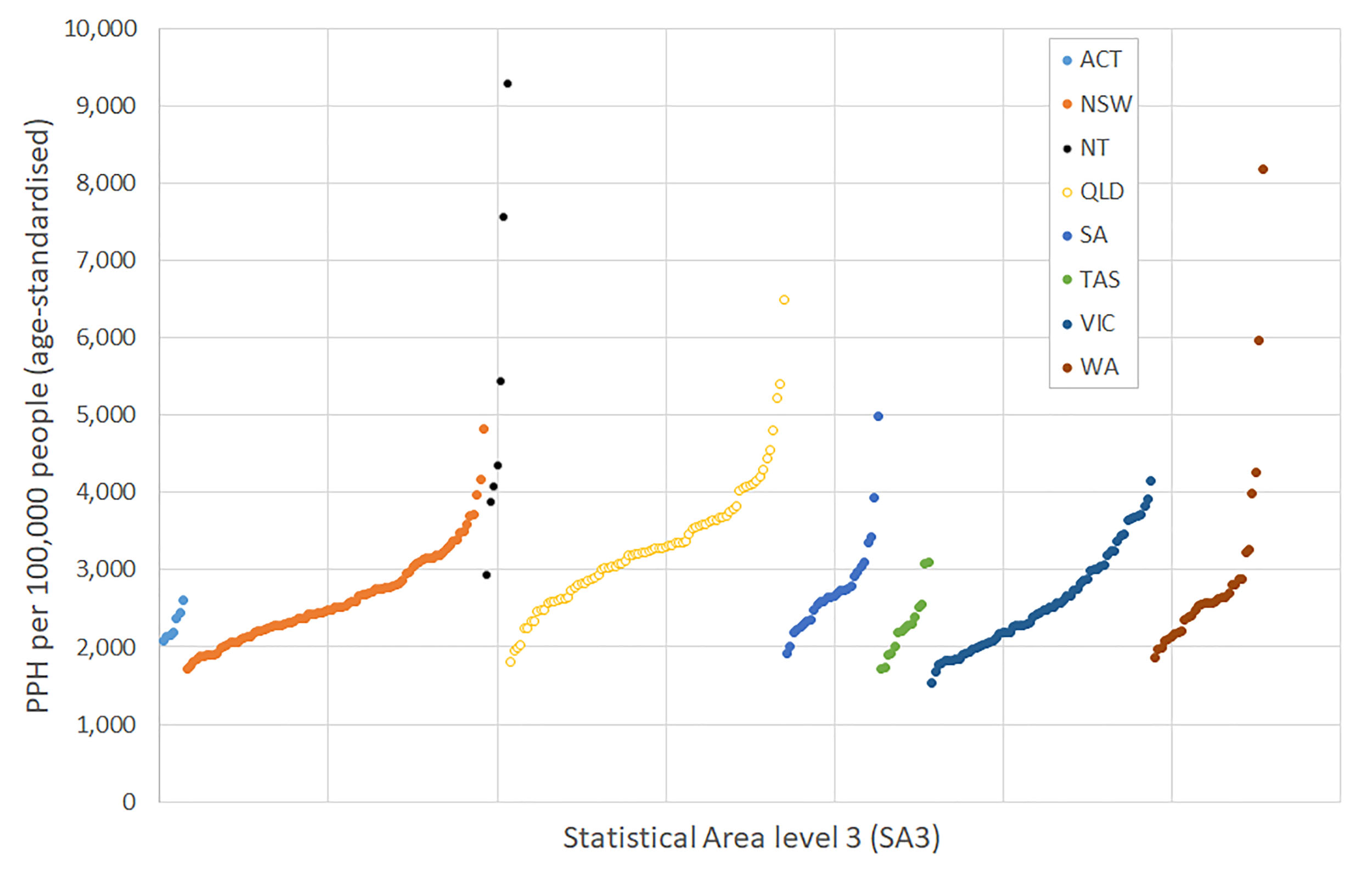

The AIHW also report PPH by the 31 Primary Health Networks (PHN). Figure 4 shows the trends in PHN data (AIHW, 2018e) highlighting the variation of rates both within and between for the Total, Acute, Chronic and Vaccine-preventable PPHs at the PHN level for 2016-17.

[1] The first character of the PHN identifier signifies the state or territory (1 = New South Wales, 2 = Victoria, 3 =Queensland, 4 = South Australia, 5 = Western Australia, 6 =Tasmania, 7 = Northern Territory, 8 = Australian Capital Territory).

The rates for Acute and Chronic PPH categories within a large proportion of PHNs were similar, shown by the tight fit of the two trend lines. However, the rates of both Acute and Chronic PPHs differed noticeably between PHNs, from just under 1,000 PPH per 1,000 population to over 2,500 PPH per 100,000 population. The lower rate magnitude and flat trend line for the Vaccine-preventable PPH category suggests rates were fairly constant across the majority of PHNs. Viewing the Total PPH category by the 327 Australian Bureau of Statistics defined Statistical Areas Level 3 (SA3) highlights the variation in rates within and between the states and territories (Figure 5).

[2]Note that the 13 SA3s for which rates were suppressed by the AIHW have been removed (AIHW, 2018e).

Apart from the Australian Capital Territory (ACT), each state and the Northern Territory exhibits some large outlying values. It is important to note that the variation may be attributable to the composition of the underlying population. For example, rates of PPH are unevenly distributed throughout the population by age and sex (PHIDU 2018). There is a distinct difference between PPH categories with older people having higher PPH rates and a greater number of admissions for chronic conditions while younger people have a greater number of admissions for acute conditions. Disparities have also been found by levels of Indigenous Status, remoteness and socioeconomic disadvantage (Page et al. 2007; Harrold et al. 2014; Banham et al. 2017; PHIDU 2018). In the Northern Territory and remote areas of Queensland and Western Australia, Indigenous Australians make up a relatively larger proportion of the population. As noted above, in 2016-17, PPH rates for the Indigenous population were three times the rates for other Australians and five times the rate for Vaccine-preventable conditions (AIHW 2018e). Those living in Remote and Very remote areas, where primary care supply and access may potentially be limited, had PPH rates of 43 and 67 per 100,000 persons. This is compared to the PPH rate in the Major cities of 26 per 100, 000 persons.

Those residents living in the most disadvantaged areas had rates of 33 per 100,000 persons while those living in the most advantaged areas had rates of 22 per 100,000 persons. Katterl et al. (2012) highlight that individuals from socioeconomic disadvantaged backgrounds have poor health, low health literacy levels and difficulties in accessing primary care. Several studies have shown a strong relationship with low individual and area levels measures of disadvantage and high PPH rates (Rosano et al. 2012; Ansari et al. 2012; Mercier et al. 2015; Falster et al. 2015). Because there is a clear link between low socioeconomic status and higher burden of illness (PHIDU 2015) , rates of PPH have also been found to be more reflective of the gradients of health, the progressive course and complications of an illness, and the impact of multimorbidity and health behaviours than of poor access to healthcare (Falster et al. 2015; Manski-Nakervis et al. 2015; Tran et al. 2014). Dantas et al. (2016) highlighted that the risk of an avoidable hospitalisation increased by a factor of 1.5 for each additional chronic condition and 1.55 for each additional body system affected. Diseases of the respiratory and circulatory systems increased the risk by 8.72 and 3.01 respectively. These results seem contrary to the premise of using PPHs as an indicator for primary care but the results are dependent on how access is defined and measured i.e. distance to primary care provider or frequency of use. Rather than how quickly a person can be seen in primary care, these higher rates may be more to do with the limited access to planned, organised care for the review and management of a chronic condition (Manski-Nakervis et al. 2015). This possible explanation is reinforced by findings that the rate of PPHs for patients with diabetes was significantly lower across defined GP usage clusters which were based on a more comprehensive definition of usage, although the trend was non-linear (Ha et al. 2018). Other health system factors, such as hospital type also have influence on rates of PPH admissions (Falster et al. 2019). Therefore, against this varied background of additional drivers of PPH rates, it would seem appropriate to pay careful attention to the reliability of the approach as a measurement indicator for quality monitoring purposes (Busby et al. 2015; Sundmacher et al. 2015).

Of significance is the reporting of substantial geographic variation of PPH rates at small area geographies by PPH categories and conditions over time (Page et al. 2007; AIHW 2018e; PHIDU 2018). This information is of relevance to policy makers and internationally has been used to identifying priority areas for commissioning (Busby et al. 2017a) and primary care organisation (Mercier et al. 2015) based on variations in quality and pathways of care.

Building on this geographical approach and incorporating a temporal approach, the Grattan Institute undertook the ‘Perils of Place’ study to identify geographic and temporal trends of PPHs in small geographical areas of Queensland and Victoria (Duckett and Griffiths 2016). The study provides a framework to identify the existence of areas with persistently high PPH rates over time, which they designate as “PPH hotspots” and provides core principles to highlight areas where interventions can be targeted. A major recommendation from the study was that a multi-year baseline at the small area level be established over time so that intervention trials can be established. This recommendation has stimulated other state-based hotspot analysis of PPH rates in South Australia (HPC 2017) and Western Australia (DOHWA 2017; Gavidia et al. 2017).

Approach, methods and output

The ‘Perils of Place’ study undertaken by the Grattan Institute (Duckett and Griffiths 2016) identified the geographic and temporal trends of PPHs at small area scale within Queensland and Victoria. The approach relied on five principles to identifying hotspot areas:

- The first principle focused on outcomes they could do something about. This was a narrowing of focus to Potentially Preventable Hospitalisations.

- The second principle looked at creating an evidence base of substantial disparity in PPH across geographical areas. This was created by calculating annual area level rates for one or more PPH condition(s) and then comparing these rates to a benchmark rate. Areas with rates that were higher than the benchmark may warrant an intervention to reduce the rate. It is worth noting here that much can be learned from areas with rates lower than the benchmark and these may warrant further investigation to understand why these rates are indeed lower.

- The third principle investigated the persistence of these rates over time. To be worth allocating resources to areas identified as hotspots, the rates of these areas must be consistently over the benchmark over time rather than just intermittently.

- Given that an area satisfies these first three principles, a further two principles make an area identified as a hotspot more amenable to action. The first of these, is that a persistent hotspot defined from past data is predicted to be a persistent hotspot into the future. This means undertaking a greater investigation into what are the potential drivers of the persistent hotspot area, i.e., primary care accessibility, the specific characteristics of the PPH (e.g., demographic composition or readmission rate) and/or the area-based characteristics (e.g., level of disadvantage or remoteness).

- Lastly, hotspots must have a big enough health and/or financial impact to warrant action. This can be in the form of reducing the absolute numbers of individuals affected or focusing on conditions of high severity. Additionally, there might be effort to concentrate on efficiency gains through targeting high concentrations of individuals at risk, or equity gains through targeting entrenched place-based problems. These efforts must all be balanced against the costs involved before grounds for intervention can be established.

Aim

In this study we focus on creating a multi-year baseline of the geographic and temporal persistence of PPHs at the small area level across the continent of Australia based on the first three principles of the Grattan Institute study. Visualisation of the data will enhance the understanding of PPH occurrence across Australia and provide a base dataset which can be used to investigate the final two Grattan Institute principles

Data

PPH data were provided to PHIDU by the AIHW, on behalf of the state and territory health departments, from the National Hospital Morbidity Database for the five years 2012-13 to 2016-17. These data have been published previously by PHIDU on an annual basis. The dataset comprised all individual patient admissions to all private and public acute hospitals, a total of 50,829,982 records. A total of 3,205,208 were flagged as potentially preventable conditions accounting for around 6% of all hospital admissions, a rate that was stable over the five years of data. PPHs were defined in accordance to the Council of Australian Governments’ National Healthcare Agreement PI 18 – Selected potentially preventable hospitalisations, 2016. The Agreement identifies 22 categories, as in Table 9, above. These are Angina (5.9% of all PPHs), Asthma (4.7%), Bronchiectasis (1.0%), Congestive Cardiac Failure (CCF)(8.9%), Cellulitis (9.4%), Convulsions and Epilepsy (5.7%), Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD) (10.7%), Dental Conditions (10.3%), Diabetes (6.8%), Ear, Nose and Throat Infections (ENT) (6.3%), Eclampsia (0.01%), Gangrene (1.7%), Hypertension (1.5%), Iron Deficiency Anemia (7.5%), Nutritional Deficiencies (0.1%), Pelvic Inflammatory Disease (PID) (0.7%), Rheumatic Heart Diseases (0.5%), Urinary Tract Infections (UTI) (11.3%), Perforated/Bleeding Ulcer (0.9%), Pneumonia and Influenza (vaccine-preventable) (2.7%), Pneumonia (Not Vaccine-Preventable) (0.3%) and Other vaccine-preventable conditions (3.0%).

Records where age group and area of residence was not reported were removed from the analysis, representing 246,180 records for all admissions and 21,092 records that were classified as PPHs. This left a total of 50,583,802 records for analysis, of which there 3,184,116 were PPH records, comprising 6.3% of all admissions.

Methodology

We built our methodology on the foundation methodology developed by the Grattan Institute in their Perils of Place study. This study investigated the spatial and temporal trends in ten years of PPHs for Victoria and Queensland. In our study, we enhanced the processes to reflect the Australian based context, PHIDUs geographical areas, a hotspot classification scheme that provided a range of heat values, a differentiation in hospital admission type and the development of interactive web-based maps and interpretive heat map graphics for in-depth visualisation of the PPH indicator.

The geography used was the Population Health Area (PHA), a small geographical area developed by PHIDU for the presentation of population health data across Australia. PHAs are comprised of a combination of either whole Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) Statistical Areas Level 2 geographic areas (SA2s) or multiple (aggregates of) SA2s. A total of 42.8% of PHAs are comprised of one SA2, 37% of two, 14.3% of three and 5.9% of four or more SA2s. We removed PHAs with populations of less than 500 persons from the analysis.

As to data selection, we focused on population-based conditions and removed the female specific conditions of Eclampsia and Pelvic Inflammatory Disease. We also disaggregated the PPHs by admission type into Same-day and Overnight stay admission types. This differentiation was used to identify hospitalisations where the condition of the patient was less severe and therefore could potentially be more amenable to the potentially protective effect of stronger primary care and more likely to be less resource intensive. For example, in 2016-2017 (AIHW 2018e), around 35% of all PPH admissions were Same-day admissions. The percentage of PPH that are Same-day varies by condition, with dental conditions and iron deficiency anaemia having percentages above 80%. Of the Same-day admissions, 52% are Acute admissions, comprising of dental conditions (24.6%) and ENT and UTI infections (at around 8% each). The Chronic category made up 44% of all Same-day admissions with Iron deficiency anaemia 19.8% of all Same-day hospitalisations followed by Angina, Asthma and Diabetes complications at around 5%. Around 4% of all Same-day admissions were for Vaccine-preventable conditions. Overnight stays represented 65% of all PPH admissions, with 49%, 42% and 9% of these Overnight admissions in the Chronic, Acute and Vaccine-preventable categories, respectively. In the Chronic condition category, Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD) and Congestive Heart Failure (CHF) represented 15% and 12% of all Overnight stay admissions, respectively. The Acute category conditions Cellulitis and Kidney and Urinary Tract Infections (UTI) made up 12% and 11% of all Overnight stay admissions, respectively. Pneumonia and Influenza (Vaccine-preventable) made up 5.8% of all Overnight stay admissions

We created datasets for all, Same-day and Overnight admission for (1) all PPHs, (2) the three categories of PPHs; Acute, Chronic and Vaccine-Preventable and (3) 20 individual PPH conditions. This provided 72 combinations of PPHs (“PPH combinations”).

To identify the geographic and temporal persistence of high rates of PPHs, we undertook five steps.

- The first step involved calculating the annual direct age-standardised rates of admissions for the PPH combinations for each PHA.

- The second step involved deriving ratios between these values and the annual direct age-standardised rate for Australia. For example, values of 0.5 or 1.5 meant a rate that was 50% lower or 50% greater than the Australian rate while values of 2 or 3 meant rates were two to three times greater than the Australian rate.

- The third step compared these ratios to a range of thresholds. This was undertaken to understand the sensitivity of the PPH combinations within the PHA for each year and discern the disparities between PHA. A total of 20 thresholds were selected with the lowest threshold set to 50% of the Australian rate and the highest set to four times the Australian rate for each year. We recorded a value of one, when the ratio was higher than each threshold while a value of zero was recorded when it was lower over the five years of analysis.

- In the fourth step we aggregated the five years into a five-digit code for each PHA by PPH combinations. This created unique codes of when the PHA was either above or below a chosen threshold for the five years, as a whole. The codes were then classified into five categories; Cold, Cold-Warm, Warm, Warm-Hot and Hot based on an aggregation rule (Table 10).

- This final step produced a dataset summarising the heat of PPH combinations by PHA and threshold. This information was used for input into the interactive web-based maps and heat map graphs.

| Classification | Codes | Aggregation rule |

| Cold | 00000,00100,01000,10000 | Never above or only one occurrence in the years 1 to 3 |

| Cold-Warm | 00001,00010,00101,01001,01010,10001,10010,10100,11000 | One occurrence in years 4 or 5 and two occurrences in the 5 years with only consecutive occurrences in year 1 and 2 |

| Warm | 00011,00110,01100,11100 | Two occurrences in the 5 years with consecutive values in years 2-5. Three occurrences in 5 years in only years 1-3 |

| Warm-Hot | 00111,01011,01101,01110,10011,10101,10110,11001,11010 | Three occurrences in the five years with at least one occurrence in the last two years. |

| Hot | 01111,10111,11011,11101,11110,11111 | Four and five occurrences in the five years. |

Output

The output for this project comprises of:

- Excel workbooks with datasheets for each PPH combination.

- Interactive atlas(es) of PPH combinations showing the geographic distribution of heat of PPH combinations by PHA across Australia.

- Heat map graphs of Acute, Chronic and Vaccine-Preventable categories and corresponding individual conditions for each PHA.

Benefits and limitations

Benefits

The major benefit of the PPH indicator(s) is their ease of creation and the up-to-date temporal currency gained from regularly collected hospital admission records (Falster and Jorm 2017). This process provides large sample sizes and the ability to link records longitudinally, if needed. The Australian dataset has a broad national coverage with a small area level geography making it suitable for identifying areas to further study and target interventions. The collection of records also adheres to a relatively consistent standard benchmark for disease coding, all of which allows for a moderate degree of reliability in geographic and temporal comparison of data at the small area level.

Limitations

Given its place in policy and funding decisions and its usage over the last 30 years, it is important to highlight that the indicator does have a variety of limitations.

Prevalence rather than health system performance?

It is important to recognise that the indicator is a population-based measure developed from a national database of hospital admissions developed to reflect health system performance. The indicator is not a measure of condition prevalence nor has the measure been adjusted for prevalence of a condition. Therefore, the measure may represent prevalence of a condition in the population rather than health system performance (AIHW 2018c). Pollmanns et al. (2018) suggest that the PPH rates should be adjusted by prevalence and unadjusted rates should be used with caution. However, reliable prevalence rates at small area levels are difficult to obtain.

Issues with data consistency

Changes to hospital admission policies and practices over time will influence how a patient is managed in a jurisdiction and then recorded as a PPH admission, i.e. whether a patient is admitted, or is treated in an outpatient or an emergency department setting (AIHW 2018c). Changes over time in the way PPH are defined also pose problems. Changes have been made in diagnostic classifications; for example, changes to the coding standard for diabetes (AIHW 2018c) and the reporting of additional diagnoses for hepatitis (AIHW 2018b) have resulted in fluctuations and increases in the reporting of diabetes complications and Vaccine-preventable conditions over time.

Calculation of rates - rare conditions and small populations

The creation of the indicator rates for admissions where PPH are rare for specific conditions must be interpreted with caution. National average rates used as benchmarks will be small and any rates calculated for small geographical areas may be randomly above the national average rate as a result of there being only one or two occurrences. This has led to the removal of rare conditions from detailed analyses (Duckett and Griffiths 2016). The creation of indicator rates at the small area geography also poses issues. Calculating rates for areas with low residential populations will over inflate the results. Combining this issue with PPH conditions that are rare will also pose erroneous results.

Readmissions

Within small geographies, the indicator can be biased by individuals who have had many admissions or readmissions which can heavily influence the population-based rate. This reflects that the indicator is based on the number of hospitalisations rather than the number of individuals hospitalised (AIHW 2018c). The frequency of these occurrences will be greater for patients with chronic conditions who have complex health needs. Banham et al. (2010) showed that a relatively small number (23%) of public hospital patients experience multiple separations but that they accounted for almost half the total PPH separations in their study. Individuals experiencing multiple separations were older, male, Indigenous or living in areas of either greater disadvantage or remoteness. Duckett and Griffiths (2016) report that tackling readmissions will be part of the solution in some places but not in others, as different problems occur in different places. They found that readmissions were more common in areas of high PPH rates over time than other areas, but there was no linear relationship between an area's PPH rate and the proportion of admissions that are readmissions. Additionally, they also found that readmissions made up a larger proportion of chronic PPH conditions than for other PPH conditions.

Face and construct validity - the effectiveness and usefulness of the indicator

PPH are identified by specific admission diagnoses derived from expert opinion as being “potentially” preventable. Several authors have questioned the face validity of these indicators, i.e. the extent to which the measure appears to measure the construct of interest. Solberg et al. (2015) suggested that while expert opinion was a reasonable way to explore the concept, there were no follow-up empirical studies to test how frequently each condition on the list was indeed preventable. This has left users to accept the conditions on face value. Of a similar nature, is that the indicator is a population level measure based on a specific admission diagnosis and therefore cannot be used to assess the preventability of individual admissions (Longman et al. 2015). Falster and Jorm (2017) offer a similar criticism suggesting that there is some uncertainty between what actual number of hospitalisations can be prevented through the access to more effective management and those that have received optimum management in primary care but still went to hospital. Additionally, a PPH admissions could be considered part of their care given a clustering of other hospitalisations and health events around the PPH admission (Falster et al. 2015). They define this as an issue of poor specificity should the indicator be interpreted as an isolated ‘preventable’ health event. The uncertainty in the indicator’s effectiveness highlighted by these authors is reflective of the definition of a PPH; that not all admissions are preventable but due to their definition are deemed “potentially” preventable.

Only a limited number of studies have investigated whether PPH admissions were indeed preventable by improved GP access or management. Fleetcroft et al. (2018) investigating emergency admissions to hospital characterised as “unplanned” admissions found that 28% of these were coded as a PPH while 13% were deemed preventable by a review of patient-case details from the treating primary practice team. The agreement between both definitions of what constituted a preventable admission was low, demonstrating a marked difference in what was avoidable based on the coded definition after the admission and those that provided the care. Additionally, a study into uncomplicated hypertension (Walker et al. 2017), based on medical chart review found a low proportion of these conditions to be avoidable (32.9%, 6.1% and 26.8% from the three physician raters) with poor to fair agreement between the raters. Two studies used an expert opinion group consensus approach to determine the preventability of PPH. Freund et al. (2013) found that 41% of ambulatory care sensitive conditions (ACSCs) were potentially avoidable. Importantly, comorbidities and medical emergencies were frequent causes attributed to ACSC-based hospitalisations but were rated as being unavoidable. Sundmacher et al. (2015) found that 27% of all hospital cases to be sensitive to ambulatory care and 20% of all hospital cases to be actually preventable. In Australia, 40% of a New South Wales cohort with chronic PPH were found to be preventable by medical review (Passey 2018).