Indigenous Potentially Preventable Hospitalisations; identifying hotspots of inequalities

A Geographic and Temporal Analysis

Published: 2020

“We're a big country, you can’t possibly average out, in a meaningful way what happens from you know Cape York to Tasmania to Perth sort of thing, and I actually think communities are tired of being put into that basket, and part of the kind of the move towards self-management is about our data and what we need.” - response of an Indigenous knowledge broker to the relevance of the Indigenous Burden of Disease to the local, Indigenous context, and to community health services (Katz et al. 2017).

Introduction

The provision of timely and effective primary health care to Indigenous people is one option to manage a population whose health status is far below that of non-Indigenous Australians. For example, there is a high proportion of individuals with chronic conditions which require continuous management and who have higher rates of hospitalisations and lower rates of access to primary care services.

Information as to the degree to which a population receives timely, accessible, and quality primary and community-based care can be reported in the form of an indirect measure, the Potentially Preventable Hospitalisations (PPH) indicator. PPH is an admission to hospital for a condition where the hospitalisation could have potentially been prevented through the provision of appropriate individualised preventive health intervention and early disease management usually delivered in primary care and community-based settings (including by general practitioners, medical specialists, dentists, nurses and allied health professionals) (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2018a).

Current comparisons show that rates of Indigenous PPH have increased over time and are far higher than those of the non-Indigenous population. The magnitude of rates of PPH conditions vary geographically over State and Territory.

The published data, as discussed in the ‘Comparisons of Indigenous to non-Indigenous Potentially Preventable Hospitalisation Rates’ section, report that PPH rates vary geographically. These variations are also reflected in the PPH literature where different evidence bases have been established in different regions of the country reflecting the location specific issues associated within these areas. For example, research in New South Wales was primarily based on Indigenous people living in urban areas. This compares to the evidence base created for the Northern Territory where the majority of research focused on Indigenous people living in remote areas.

Of significance is the reporting of substantial geographic variation of PPH rates at small area geographies by PPH categories and conditions over time (Page et al. 2007; Public Health Information Development Unit, 2018; Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2019d). Highlighting their distribution geographically can identify areas of concern. A high rate of PPHs may indicate an increased prevalence of the conditions in the community, poorer functioning of the non-hospital care system or an appropriate use of the hospital system to respond to greater need (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2018d). Alternatively, it is also important to investigate why in other instances rates are low. This information is of relevance to policy makers and internationally has been used to identifying priority areas for commissioning (Busby et al. 2017a) and primary care organisation (Mercier et al. 2015) based on variations in quality and pathways of care.

Study Outline

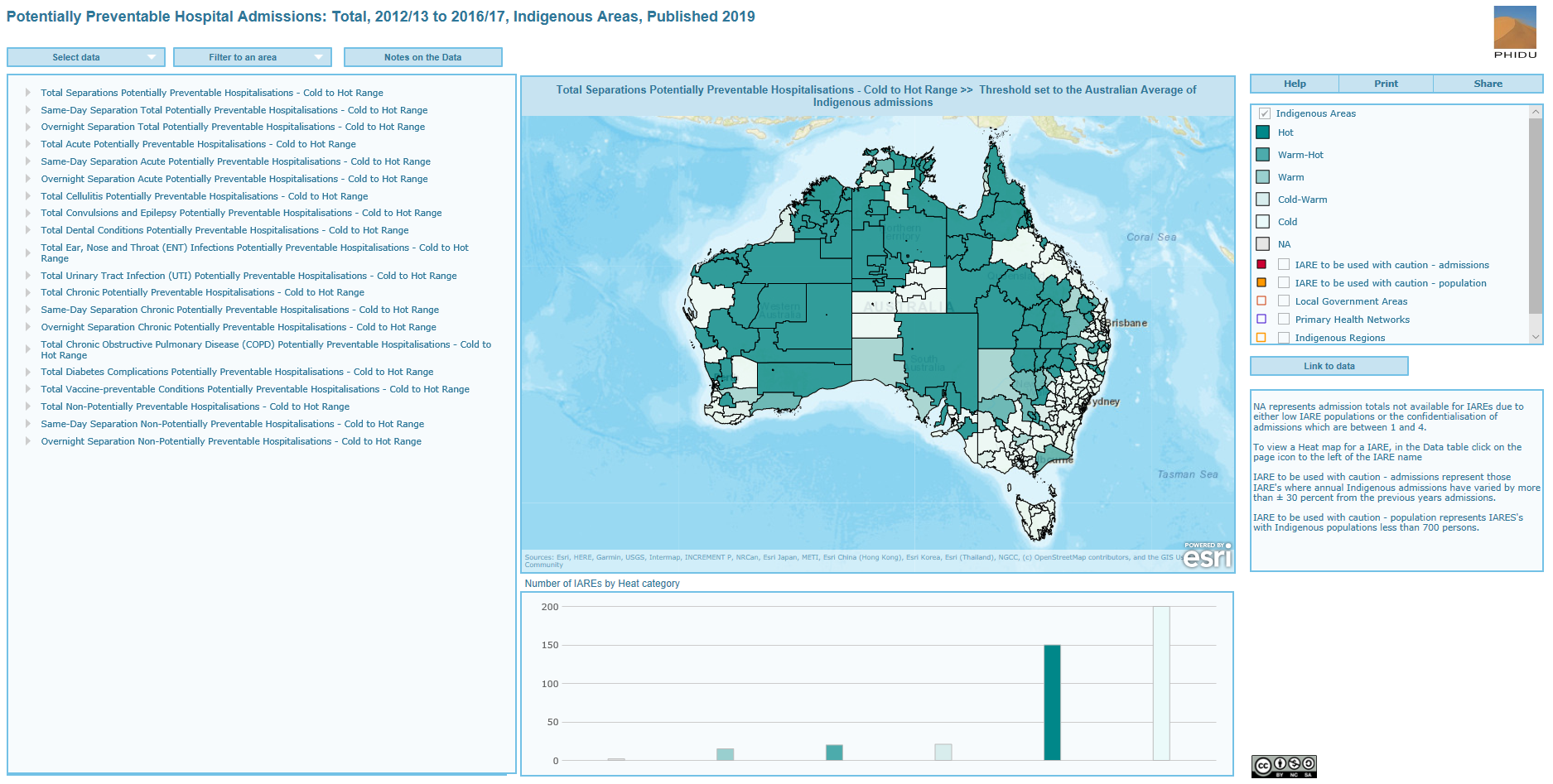

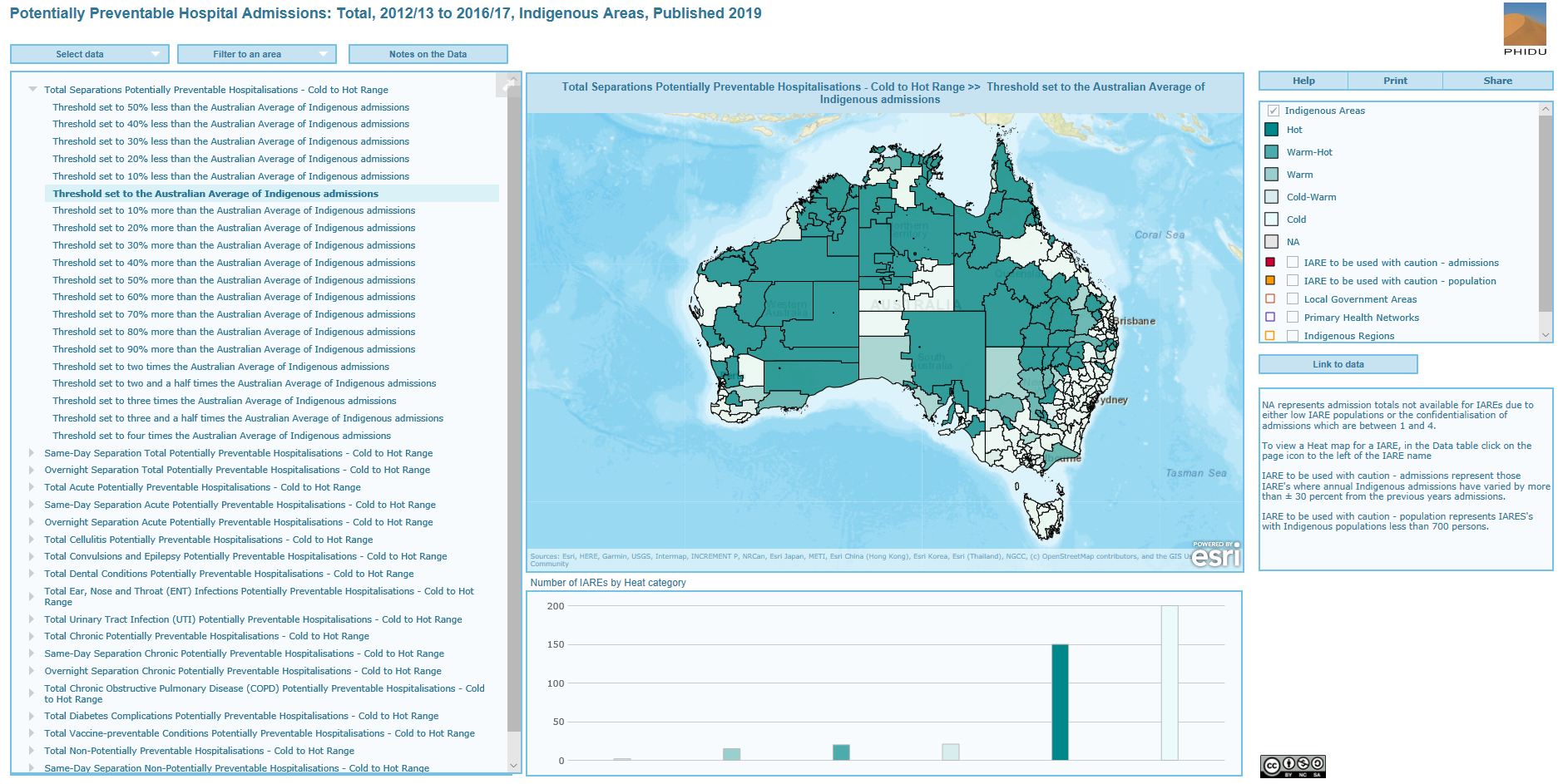

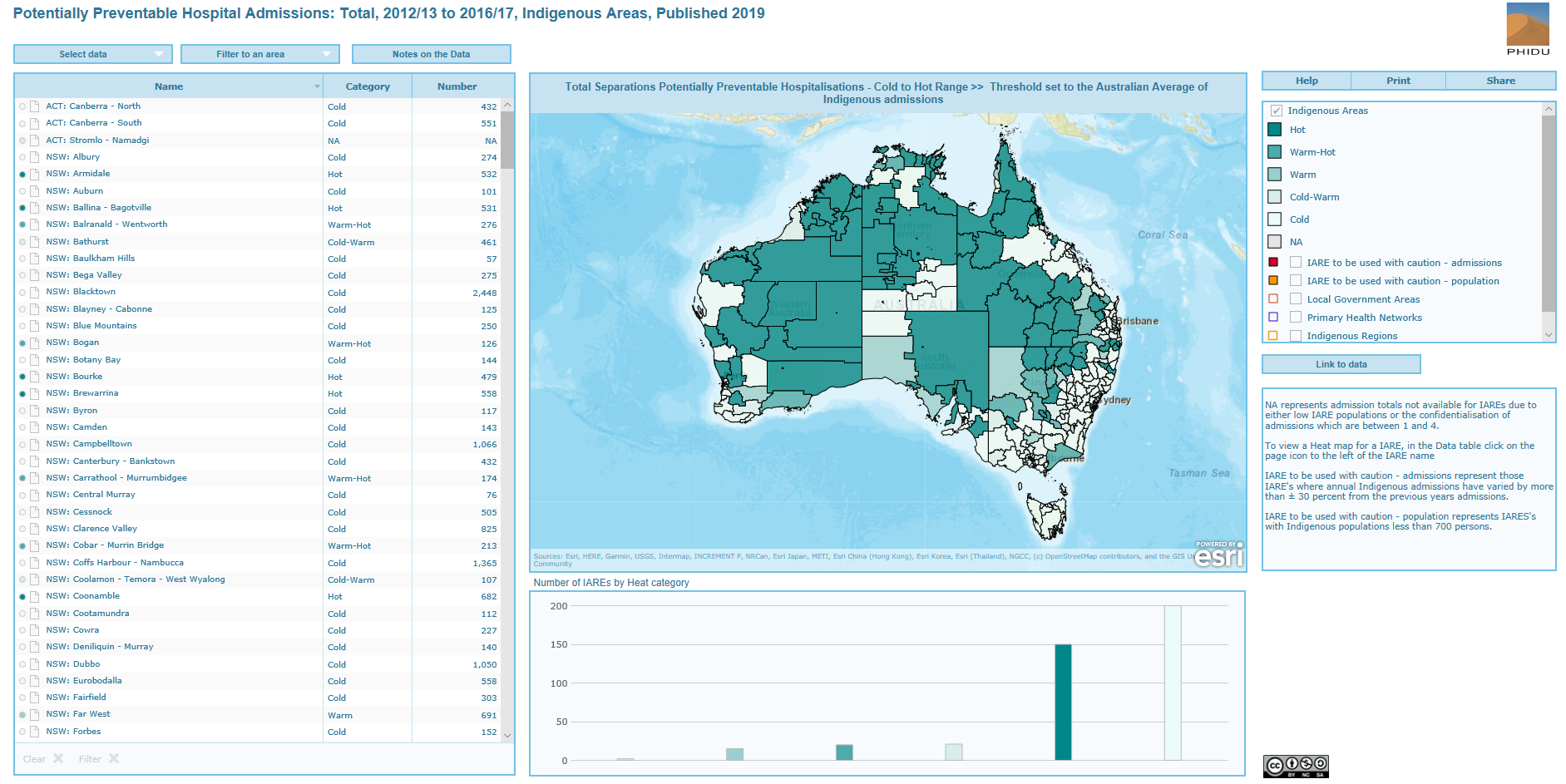

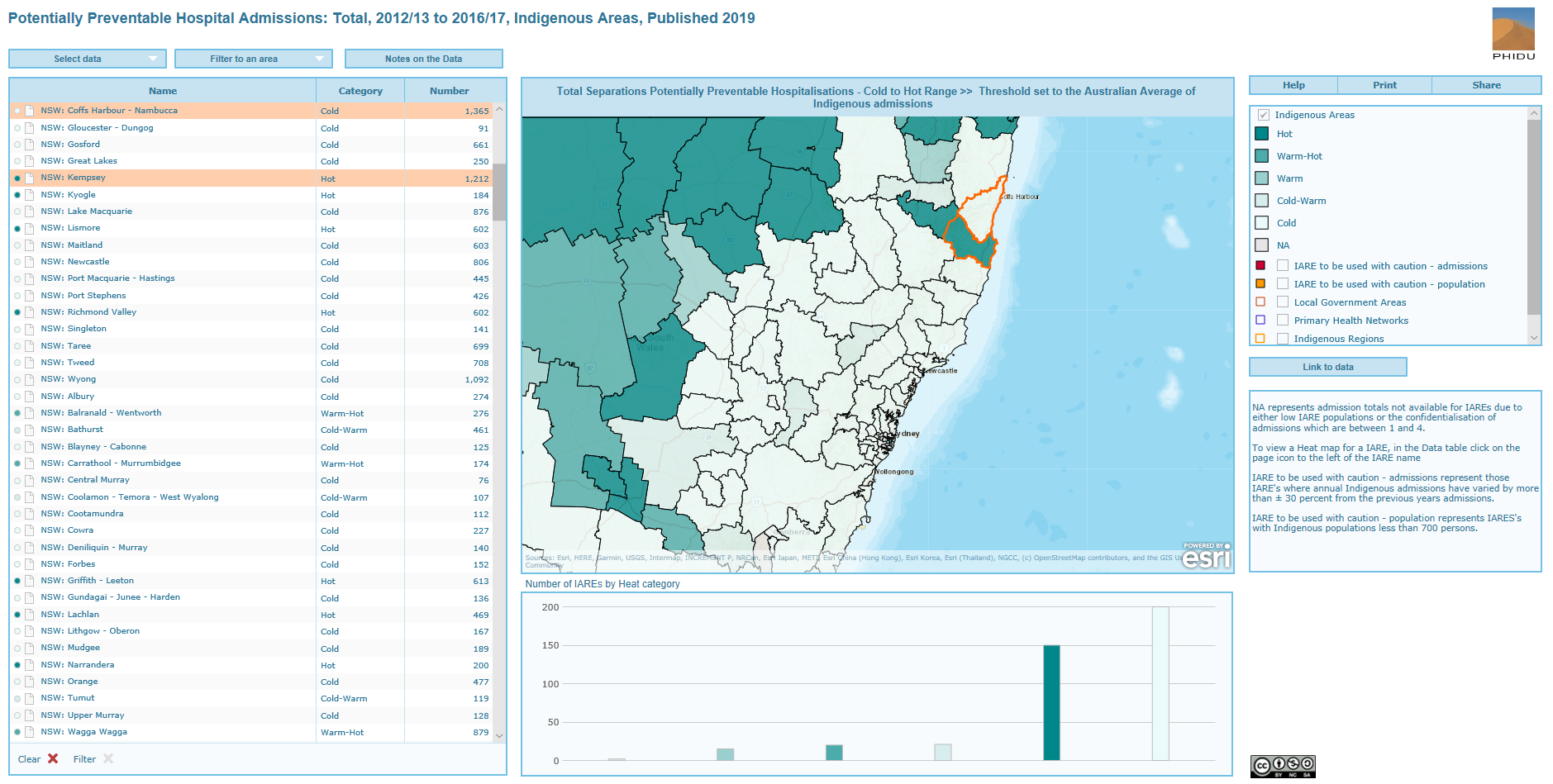

This study focuses on creating a multi-year baseline of the geographic and temporal persistence of Potentially Preventable Hospitalisations (PPH) for the Indigenous population at the small area level across Australia. It follows on from previous analysis of PPHs for the Australian population as a whole drawing on the work by Duckett and Griffiths (2016) published as “Perils of Place: identifying hotspots of health inequalities”. The Duckett and Griffiths study provides a framework to follow to identify “PPH hotspots” based on the existence of areas with persistently high rates of PPH for Indigenous Australians over time. The data and methodology used are available here .

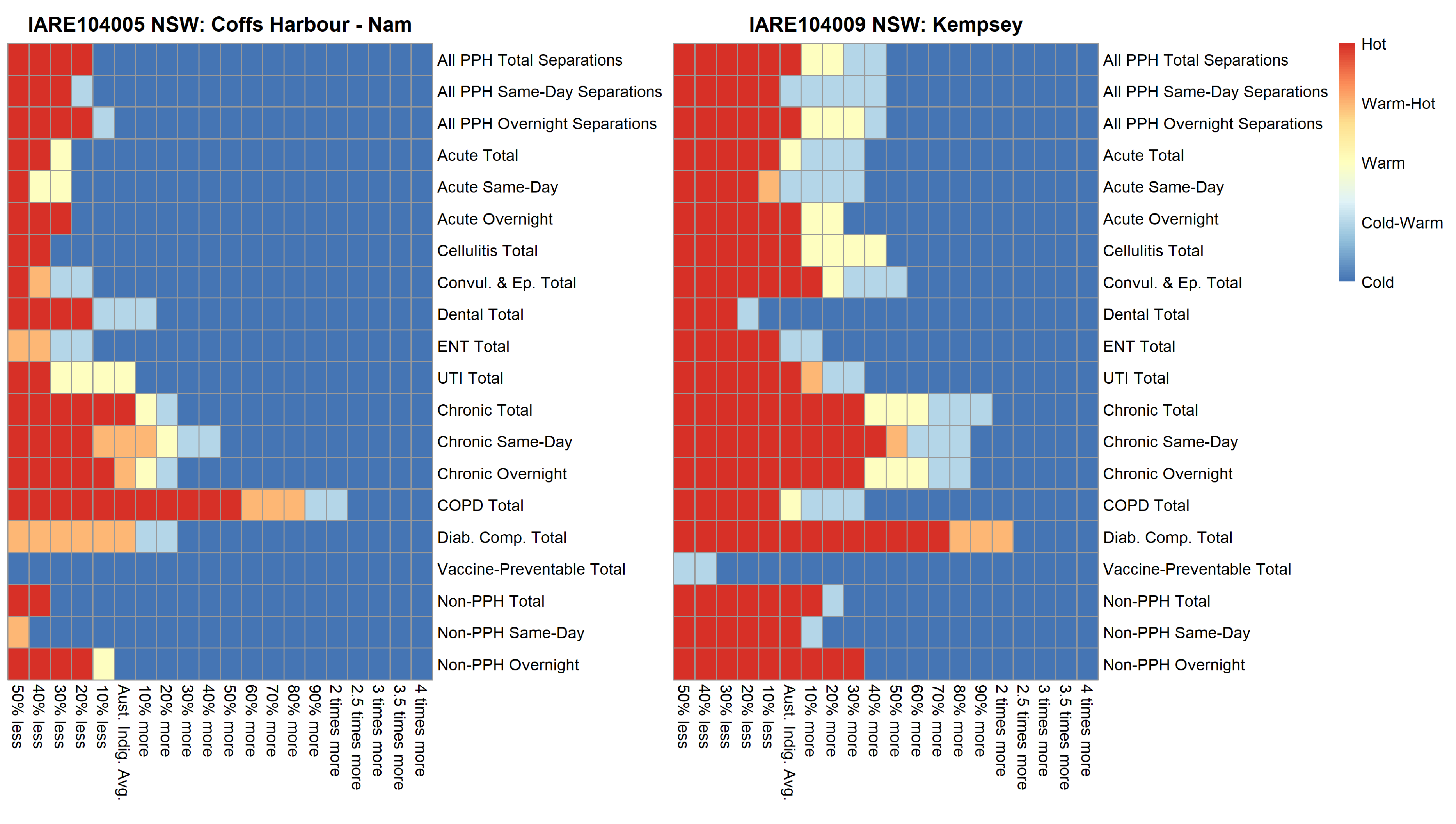

We hope that this new analysis, and its presentation in geographical maps, heat map graphs and data sheets, will provide information that is useful to the various levels of the health system, from state and territory health agencies to local and regional health networks and boards, PHNs and primary care practitioners, in working together with an aim to reducing the level of Indigenous PPHs through improved primary health care outcomes at the local area level. The interpretation of the data and its presentation is complex, and we encourage users to read the detailed notes , and, to take note of the section on Using the Atlas. Further information can be obtained by contacting the Public Health Information Development Unit.

The current status of health

The impact of colonisation and settlement has been a major cause of the gap in health between the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander (referred to here as Indigenous) and the non-Indigenous population. Indigenous Australians currently experience poorer health status than non-Indigenous Australians with a burden of disease that was 2.3 times the rate of non-Indigenous Australians (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2016). In reporting on their day-to-day health, Indigenous Australians were twice as likely as non-Indigenous Australians to report their health as fair or poor (Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2016). The Australian Health Ministers’ Advisory Council, 2017 report highlighted that 29% of Indigenous Australians aged 15 years and over had three or more long-term health conditions and had higher rates of chronic disease. Chronic diseases were responsible for 64% of the total disease burden for Indigenous Australians and 70% of the gap between Indigenous and non-Indigenous health in 2011 (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2016). For diseases like diabetes, rates were 3 times higher than the non-Indigenous rate and of those diagnosed with diabetes 61% had high blood sugar levels (Australian Health Ministers’ Advisory Council, 2017). Risk factors such as alcohol consumption, smoking, unhealthy weight and high blood pressure were highlighted as more prevalent among Indigenous Australians than non-Indigenous Australians. For example, 42% of Indigenous Australians aged 15 years and over reported that they were current smokers and 66% of these people were reported as being overweight or obese. As a result, these figures represent Indigenous rates of 2.7 times higher for smoking and 1.6 times as likely to be obese when compared to non-Indigenous Australians. This lower health status reflects that Indigenous people were more than twice as likely to be hospitalised (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2019) and have a significant lower life expectancy with Indigenous males' life expectancy estimated at 10.6 years lower than non-Indigenous males and 9.5 years lower for females (Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2013). The gap in premature mortality is substantial, with the age-standardised death rate for Indigenous people less than 75 years of age 2.7 times that for the non-Indigenous population between 2011 and 2015 (Public Health Information Development Unit, 2019). Furthermore, the death rates for Indigenous people whose age was less than 55 years and 65 years were 4.1 and 3.9 times those for the non-Indigenous population.

Connectedness to family and community, land and sea, culture and identity have been identified as integral to health from Indigenous perspectives (National Aboriginal Health Strategy Working Party, 1989). Since a large proportion of Indigenous Australians live outside of the metropolitan area, their geographic location influences a range of factors such as their social and environmental context, cultural identification and social networks through to educational and employment opportunities (Australian Health Ministers’ Advisory Council, 2017). Remoteness of their residence also influences their health and access to health services including primary health care services. The Australian Bureau of Statistics defines Remoteness as one of five categories. These are Major Cities of Australia (all capital cities other than Hobart and Darwin), Inner Regional Australia (Darwin, Hobart, and urban fringes), Outer Regional Australia, Remote Australia and Very Remote Australia (Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2018).

Evidence from the 2011 Indigenous burden of disease study (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2016) found that Remote Australia had the highest rate of Indigenous burden which was 2.4 times that for non-Indigenous Australians. This was followed by Very Remote Australia with a rate of 1.9 times the burden of non-Indigenous Australians. The Inner Regional Australia category had the lowest rate of total burden for Indigenous Australians, but rates were still 1.7 times higher than non-Indigenous Australians. The gradient in burden of disease by remoteness also persisted by disease type. For example, Indigenous adults in Remote Australia had higher rates of diabetes than in non-remote areas (Australian Health Ministers’ Advisory Council, 2017). The associated direct health expenditure for Indigenous Australians has been estimated at $8,515 per person in 2013-2014, 38% higher than for non-Indigenous Australians ($6,180) (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2018). The differences likely reflect the management of the higher underlying disease burden of Indigenous Australians, their limited access to early detection and non-hospital alternatives in remote areas, and to some extent the higher costs of delivering health services in rural and remote areas (Australian Health Ministers’ Advisory Council, 2017).

The Potentially Preventable Hospitalisations (PPH) Indicator

Background and significance to health policy

Potentially Preventable Hospitalisations (PPHs) are hospitalisations for a condition where an admission to hospital could have potentially been prevented through the provision of appropriate individualised preventative health intervention and early disease management usually delivered in primary care and community-based care settings (including by general practitioners, medical specialists, dentists, nurses and allied health professionals) (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2018a). The current national standard for PPHs was agreed to in 2015 and was adopted in reporting data from 2012-13 onwards (National Health Performance Authority, 2015; 2017).

The PPH indicator(s) are officially used as a national accessibility and effectiveness health performance progress measure within the Australian National Healthcare Agreement corresponding to the outcome, 'Australians receive appropriate high quality and affordable primary and community health services' (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2018b). It is also a formal indicator within the National Health Performance and Accountability Framework (Falster and Jorm, 2017). The measure is therefore tied directly to hospital funding (Passey et al. 2015). The indicator(s) are seen by policy makers as an opportunity to undertake reform and drive innovation to improve health service delivery and clinical practice in the primary care setting. For example, analysis of PPH variation in Queensland has led the Queensland Clinical Senate to recommend that PPH data be shared with local healthcare service clinicians and their provider organisations (such as Primary Health Networks) (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2018c). Routine regional reporting has also been called for to help monitor performance and evaluate policy and program initiatives (Banham et al. 2010).

Interpretation of the measure

Potentially Preventable Hospitalisations have been researched for over 30 years and over this time the terminology and definitions have changed internationally (Purdy et al. 2009) and in Australia. Past literature reviews of the evidence base have shown that hospitalisations which have been also been defined as unplanned admissions or avoidable or ambulatory care sensitive conditions (Ansari 2007; Rosano et al. 2012) have an inverse relationship with accessibility to primary care. A focus on the literature involving chronic conditions has also reported similar conclusions (van Loenen et al. 2014; Gibson et al. 2013; Wolters et al. 2017). For the majority of PPH conditions, these literature reviews provide strong evidence of the inverse relationship between accessibility to primary care and PPH rates. It must be noted however, that the applicability of outcomes to the Australian setting was limited by the inclusion of very few Australian studies and/or a high representation of US-based studies (Erny-Albrecht et al. 2016). Interestingly for dental conditions in Australia, an empirical study found a reverse relationship with high rates of hospital admission associated with higher dentists per capita (Yap et al. 2018).The indicator(s) represent a supply-based measure, calculated as a rate of admission to hospital for the conditions. There are three broad categories of PPHs which have different interpretations of preventability (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2018d):

- Acute - conditions that may not be preventable, but theoretically would not result in hospitalisation if adequate and timely care (usually non-hospital) was received. These include eclampsia, pneumonia (not Vaccine-preventable), pyelonephritis, perforated ulcer, cellulitis, urinary tract infections, pelvic inflammatory disease, ear, nose and throat infections, and dental conditions. These conditions make up around 41% of all PPH admissions (National Health Performance Authority, 2015)

- Chronic- conditions that may be preventable through behaviour modification and lifestyle change, but can also be managed effectively through timely care (usually non-hospital) to prevent deterioration and hospitalisation. These conditions include diabetes complications, asthma, angina, hypertension, congestive heart failure, nutritional deficiencies and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. These conditions make up around 56% of PPH admissions (National Health Performance Authority, 2015).

- Vaccine-preventable- diseases that can be prevented by proper vaccination, including influenza, bacterial pneumonia, hepatitis, tetanus, diphtheria, pertussis (whooping cough), chicken pox, measles, mumps, rubella, polio and haemophilus meningitis. The conditions are considered to be preventable, rather than the hospitalisation. These conditions make up around 4% of PPH admissions (National Health Performance Authority, 2015).

Falster and Jorm 2017 report that the indicator rate can be presented in three ways; a comparison between geographic regions, a breakdown by condition and population subgroup, and a temporal trend in PPH rates. For example, in reviewing Australia’s health in 2018 (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2018), PPH rates are compared by remoteness area of residence (across capital cities, regional and remote areas), socioeconomic status of area of residence, country of birth of patient and Indigenous status. For example, Katterl et al. (2012) highlight that individuals from socioeconomic disadvantaged backgrounds have poor health, low health literacy levels and difficulties in accessing primary care. Several studies have shown a strong relationship with low individual and area levels measures of disadvantage and high PPH rates (Rosano et al. 2012; Ansari et al. 2012; Mercier et al. 2015; Falster et al. 2015). Because there is a clear link between low socioeconomic status and higher burden of illness (Public Health Information Development Unit, 2015), rates of PPH have also been found to be more reflective of the gradients of health, the progressive course and complications of an illness, and the impact of multimorbidity and health behaviours rather than of poor access to healthcare (Falster et al. 2015; Manski-Nakervis et al. 2015; Tran et al. 2014). For example, Harriss et al. (2018) found that up to 76.5% of all PPHs in their regional Queensland hospital study had underlying chronic conditions.

These results seem contrary to the premise of using PPHs as an indicator for primary care but the results are dependent on how access is defined and measured i.e. distance to primary care provider or frequency of use. Conversely, rather than how quickly a person can be seen in primary care, these higher rates may be more to do with the limited access to planned, organised care for the review and management of a chronic condition (Manski-Nakervis et al. 2015). This possible explanation is reinforced by findings that the rate of PPHs for patients with diabetes was significantly lower across defined GP usage clusters which were based on a more comprehensive definition of usage, although the trend was non-linear (Ha et al. 2018). Other health system factors, such as hospital type also have influence on rates of PPH admissions (Falster et al. 2019). Therefore, against this varied background of additional drivers of PPH rates, it would seem appropriate to pay careful attention to the reliability of the approach as a measurement indicator for quality monitoring purposes (Busby et al. 2015; Sundmacher et al. 2015).

Benefits and Limitations

Benefits

The major benefit of these indicators is their ease of creation and the up-to-date temporal currency gained from regularly collected hospital admission records (Falster and Jorm 2017). This process provides large sample sizes and the ability to link records longitudinally, if needed. The Australian dataset has a broad national coverage with a small area level geography making it suitable for identifying areas to further study and target interventions. The collection of records also adheres to a relatively consistent standard benchmark for disease coding, all of which allows for a moderate degree of reliability in geographic and temporal comparison of data at the small area level.

Limitations

Given its place in policy and funding decisions and its usage over the last 30 years, it is important to highlight that the indicator does have a variety of limitations.

Prevalence rather than health system performance?

It is important to recognise that the indicator is a population-based measure developed from a national database of hospital admissions developed to reflect health system performance. The indicator is not a measure of condition prevalence nor has the measure been adjusted for prevalence of a condition. Therefore, the measure may represent prevalence of a condition in the population rather than health system performance (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2018c). Pollmanns et al. (2018) suggest that the PPH rates should be adjusted by prevalence and unadjusted rates should be used with caution. However, reliable prevalence rates at small area levels are difficult to obtain. This issue is of relevance to the Indigenous population who have higher rates of prevalence for underlying chronic diseases. For example, in three remote Aboriginal communities in Northern Territory rates of proteinuria, high blood pressure, and diabetes were significantly higher than rates from a nationally representative sample of participants (Hoy et al. 2007).

Issues with data consistency

Changes to hospital admission policies and practices over time will influence how a patient is managed in a jurisdiction and then recorded as a PPH admission, i.e. whether a patient is admitted, or is treated in an outpatient or an emergency department setting (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2018c). Changes over time in the way PPH are defined also pose problems. Changes have been made in diagnostic classifications; for example, changes to the coding standard for diabetes (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2018c) and the reporting of additional diagnoses for hepatitis (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2018b) have resulted in fluctuations and increases in the reporting of diabetes complications and Vaccine-preventable conditions over time.

Calculation of rates - rare conditions and small populations

The creation of the indicator rates for admissions where PPH are rare for specific conditions must be interpreted with caution. National average rates used as benchmarks will be small and any rates calculated for small geographical areas may be randomly above the national average rate as a result of there being only one or two occurrences. This has led to the removal of rare conditions from detailed analyses (Duckett and Griffiths 2016). The creation of indicator rates at the small area geography also poses issues. Calculating rates for areas with low residential populations will over inflate the results. Combining this issue with PPH conditions that are rare will also pose erroneous results.

Readmissions

Within small geographies, the indicator can be biased by individuals who have had many admissions or readmissions which can heavily influence the population-based rate. This reflects that the indicator is based on the number of hospitalisations rather than the number of individuals hospitalised (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2018c). The frequency of these occurrences will be greater for patients with chronic conditions who have complex health needs. Banham et al. (2010) showed that a relatively small number (23%) of public hospital patients experience multiple separations but that they accounted for almost half the total PPH separations in their study. Individuals experiencing multiple separations were older, male, Indigenous or living in areas of either greater disadvantage or remoteness. Duckett and Griffiths (2016) report that tackling readmissions will be part of the solution in some places but not in others, as different problems occur in different places. They found that readmissions were more common in areas of high PPH rates over time than other areas, but there was no linear relationship between an areas PPH rate and the proportion of admissions that are readmissions. Additionally, they also found that readmissions made up a larger proportion of chronic PPH conditions than for other PPH conditions.

Face and construct validity - the effectiveness and usefulness of the indicator

PPH are identified by specific admission diagnoses derived from expert opinion as being “potentially” preventable. Several authors have questioned the face validity of these indicators, i.e., the extent to which the measure appears to measure the construct of interest. Solberg et al. (2015) suggested that while expert opinion was a reasonable way to explore the concept, there were no follow-up empirical studies to test how frequently each condition on the list was indeed preventable. This has left users to accept the conditions on face value. Of a similar nature is that the indicator is a population level measure based on a specific admission diagnosis and therefore cannot be used to assess the preventability of individual admissions (Longman et al. 2015). Falster and Jorm (2017) offer a similar criticism suggesting that there is some uncertainty between what actual number of hospitalisations can be prevented through the access to more effective management and those that have received optimum management in primary care but still went to hospital. Additionally, a PPH admissions could be considered part of their care given a clustering of other hospitalisations and health events around the PPH admission (Falster et al. 2015). They define this as an issue of poor specificity should the indicator be interpreted as an isolated ‘preventable’ health event. The uncertainty in the indicator’s effectiveness highlighted by these authors is reflective of the definition of a PPH; that not all admissions are preventable but due to their definition are deemed “potentially” preventable.

Only a limited number of studies have investigated whether PPH admissions were indeed preventable by improved GP access or management. Fleetcroft et al. (2018) investigating emergency admissions to hospital characterised as “unplanned” admissions found that 28% of these were coded as a PPH while 13% were deemed preventable by a review of patient-case details from the treating primary practice team. The agreement between both definitions of what constituted a preventable admission was low, demonstrating a marked difference in what was avoidable based on the coded definition after the admission and those that provided the care. Additionally, a study into uncomplicated hypertension (Walker et al. 2017), based on medical chart review found a low proportion of these conditions to be avoidable (32.9%, 6.1% and 26.8% from the three physician raters) with poor to fair agreement between the raters. Two studies used an expert opinion group consensus approach to determine the preventability of PPH. Freund et al. (2013) found that 41% of ambulatory care sensitive conditions (ACSCs) were potentially avoidable. Importantly, comorbidities and medical emergencies were frequent causes attributed to ACSC-based hospitalisations but were rated as being unavoidable. Sundmacher et al. 2015 found that 27% of all hospital cases to be sensitive to ambulatory care and 20% of all hospital cases to be actually preventable. In Australia, 40% of a New South Wales cohort with chronic PPH were found to be preventable by medical review (Passey, 2018).

Longman et al. (2015) highlights a further three issues associated with the representativeness of PPH admissions as an indicator. Firstly, whether any PPH admissions, particularly chronic PPHs, are more preventable than others. This further reiterates Solberg et al. (2015) requests of how frequently each condition on the list was indeed preventable? and what the most preventable causes might be? Sundmacher et al. 2015 goes someway to answer these questions as the “estimated degree of preventability” for ACSC hospitalisations varied from 58% to 94%. For example, the percentage estimates of preventability for Bronchitis and COPD was 76%, Ear, Nose and Throat Infections was 85%, Hypertension was 83%, Influenza and pneumonia was 68%, and Dental conditions was 94%. However, once again it was based on an expert opinion consensus method not an empirical one as hoped by Solberg et. al. 2015. Secondly, Longman et al. (2015) suggested that it was not possible to explore how the preventability of individual admission varies across different population groups or in different contexts. Lastly, they highlight that there is a timescale associated with chronic PPHs, such that care withheld earlier on in the disease progression can cause the admission now and in the future. Furthermore, while chronic conditions leading to hospitalisation may have been prevented through primary prevention initiatives (such as quit smoking interventions or physical activity programs), the long time lag between disease onset and complications leading to hospital admission means that such initiatives may take many years to impact on admission rates (Falster and Jorm 2017). These points illustrate the temporal issues of continuity of care and early intervention associated with chronic PPHs. They then lead to the overarching question of what is the right PPH rate for a specific area? Currently for an area, the rate calculated is an overestimation of the number of preventable admissions since it is unknown how many of these admissions can feasibly be prevented (Longman et al. 2015).

The measure can also be judged on its construct validity. In this case, can the PPH measure be used as an indicator to prevent hospitalisations by directing actions to improve access to and strengthening effective management of primary care. Early reviews (Basu and Brinson 2008; Katterl et al. 2012; Purdy and Huntley 2013) have highlighted some broad principles for effective initiatives to reduce PPH admissions. These are:

- Comprehensive, multidisciplinary, team based, collaborative, patient and disease-centric management programmes, particularly for the medium to long-term time period

- education based comprehensive care programmes

- interventions that aimed at increasing access, or providing a wider coverage of healthcare delivery services for all patients in the system, in particular for children, the poor and underserved

- observation units for diseases that are amenable to home based pharmacological management

- telemedicine and computer-based programmes where patients and health care providers interacted with each other

- early identification of patients who are at risk of hospitalisation

- care coordination and integration of services – continuity of care, use of practice or specialist nurses

- self-management, exercise and rehabilitation

- importance of tailoring approaches aimed at characterising and targeting PPHs to specific population or context

Importantly, Purdy and Huntley (2013) highlight that case management, specialist clinics, care pathways and guidelines, medication reviews, vaccine programmes and hospital at home do not appear to reduce avoidable admissions. A more up to date review (Erny-Albrecht et al. 2016) summarises the effectiveness of primary health care-based programmes both internationally and in Australia which have targeted potentially avoidable hospitalisations in vulnerable groups with chronic disease. It highlighted the key predictors of these types of hospitalisations, that elements of successful programmes are context and condition specific, a range of interventions that showed an assortment of effectiveness in reductions in rates of PPH and further policy considerations. It concludes that while some programmes are effective much of the trial-based evidence regarding intervention factors that impact on the rates of hospitalisation is inconclusive.

A recent literature review by Jaques et al. (2018) found that mode of delivery, intervention content, sensitivity to culture, and the inclusion of the community of interest in program design and potentially implementation and evaluation were valuable factors in effective community-based interventions aimed at reducing PPHs. Special considerations were identified for locational disadvantage with consideration needed of the target population and acknowledgement of the local social and physical environments. Implementing programs in areas of highest needs (burden of disease) and selecting venues where largest number of families can be reached as well as incorporating principles of learning and change into the program were highlighted as important principles.

Others have highlighted priority areas for change and potential points of leverage to improve GP access and quality of care (Muenchberger and Kendall 2010; Freund et al. 2013; Busby et al. 2015; Busby et al. 2017b; Longman et al. 2018). What can be gleamed from these studies is that there is no one path leading to reductions in PPH rates. Rather it will require change to a combination of complex and integrated factors to reduce rates. These include improving system-, clinician- and patient-level factors within an appropriately resourced and supported framework of comprehensive primary healthcare that is accessible, affordable, holistic, practical and evidence based (Longman et al. 2018).

The literature highlighting the benefits of providing stronger primary health care in relation to PPH conditions is progressing and interventions have been found to decrease the rates of potentially avoidable hospitalisation internationally (Wensing et al. 2018; Swanson et al. 2018).

In Australia, this reduction in hospitalisations has been found for integrated care for COPD and chronic heart failure (CHF) (Bird et al. 2010) diabetes (Zhang et al. 2015; Hollingworth et al. 2017) and chronic conditions in general (Lawn et al. 2018). In the first study (Bird et al. 2010), patients in addition to receiving normal care for COPD and CHF were provided through ‘Care Facilitators’ additional care of unmet health care needs and information, advice and education on their condition and self-management. COPD patients with this increased care reduced their emergency presentations, admissions and hospital inpatient bed stays by 10, 25 and 18% respectively. Similarly, CHF patients also demonstrated reductions of 39, 36, and 33%. The authors conclude that the intervention to provide a more integrated care facilitation model that is patient focussed, provides an education component to promote greater self-management compliance and delivers a continuum of care through acute and community health sectors, reduces the utilisation of acute health care facilities. The Zhang et al. (2015) study found that those patients that agreed to have their diabetes managed by an innovative, multidisciplinary, community-based, integrated primary-secondary care diabetes service were nearly half as likely to be hospitalised for a potentially preventable diabetes-related principle diagnosis when compared to the usual care group. Hollingworth et al. (2017), highlights that the intervention group, those that had their diabetes care through a multidisciplinary, community based, integrated primary-secondary care diabetes service at a hospital diabetes outpatient clinic recorded a 47% reduction in hospitalisations. This reduction equated to a $132.5 million cost saving when extrapolated to the Australian context in 2014.

Higher regularity of GP contact has found to reduce the rate of PPH admissions (Einarsdottir et al. 2010; Ha et al. 2018). For example, Ha et al. (2018) found that the rate of PPH was significantly lower for clusters of patients with moderate, high and very high GP usage when compared with those with no GP usage. However, no linear relationship was found with the highest effect observed among those with moderate GP usage. A further study showed that the risk of hospitalisations and secondary healthcare costs can be reduced through higher regularity of GP contact that is more evenly dispersed, not necessarily more frequent (Moorin et al. 2019). This study calculated that a reduction in cost was in the range of 23 to 41% when compared to patients who have low regular contact with their GP. Of importance is a study by Zhao et al. (2014), highlighting that a $1 spent in strengthening primary care in remote Indigenous communities could save $3.95-$11.75 in hospital costs, in additions to health benefits for individual patients.

The research highlighted above demonstrates that the utility of the PPH indicator is increasing with many examples of marked reductions in PPH conditions and significant cost savings.

Comparisons of Indigenous to non-Indigenous Potentially Preventable Hospitalisation Rates

PPH rates over time

Rates of PPH have increased over time for both Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians (Table 1). Current data show that the rates of Indigenous PPH were around three times higher than non-Indigenous PPH and this trend was similar across the time series. Rates for Acute and Chronic conditions were around 2.5 times and 3 or more times greater, respectively than for the non-Indigenous population. PPH rates for Vaccine-preventable conditions were considerably higher for Indigenous Australians with rates increasing for all Australians over the time series.

| 2013-14 | 2014-15 | 2015-16 | 2016-17 | 2017-18 | ||

| Indigenous | ||||||

| Total PPH | 53.3 | 70.7 | 73.6 | 76.4 | 79.9 | |

| Acute conditions | 24.7 | 28.2 | 30.1 | 31.1 | 31.5 | |

| Chronic conditions | 23.5 | 34.8 | 35.6 | 37.0 | 38.0 | |

| Vaccine-preventable conditions | 6.3 | 9.4 | 9.8 | 10.2 | 12.7 | |

| Non-indigenous | ||||||

| Total PPH | 16.3 | 24.3 | 25.4 | 26.2 | 26.7 | |

| Acute conditions | 9.3 | 11.8 | 12.2 | 12.5 | 12.3 | |

| Chronic conditions | 6.1 | 10.7 | 11.6 | 12.0 | 11.8 | |

| Vaccine-preventable conditions | 0.9 | 1.6 | 1.8 | 2.0 | 2.9 |

PPH rates by State and Territory

The rates of PPH also vary by State and Territory, Table 2 gives a broad geographic perspective of the distribution of PPH admissions. Supplementary data (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2017) taken from the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Performance Framework (Australian Health Ministers’ Advisory Council, 2017) report that the rates of total PPH (per 1,000 persons) in 2013-15 ranged from 24.6 per 1,000 persons in Tasmania to 117.1 in the Northern Territory. The rate ratios (Indigenous divided by non-Indigenous rates) were 1.2 times to 4.4 times the non-Indigenous population. The rates also varied by PPH category type. Rates for Vaccine-preventable conditions ranged from 3.4 per 1,000 persons in New South Wales to 27.9 in the Northern Territory; rate ratios ranged from 2.6 in New South Wales to 13.3 in the Northern Territory. Rates of Acute conditions were lowest in Victoria (16.9 per 1,000) and highest in the Northern Territory (44.1 per 1,000); rate ratios for Acute condition were lowest in Victoria (1.6) and highest in Western Australia and the Northern Territory (3.5). Rates of Chronic Conditions were lowest in Victoria (23.6 per 1,000) and highest in the Northern Territory (52 per 1,000); rate ratios were between 2.1 and 4.2, respectively. No rates for Tasmania were published for PPH category type.

| Location | PPH category-type | Indigenous | Non-indigenous | Ratio |

| New South Wales | Total PPH | 53.8 | 21.8 | 2.3 |

| Vaccine-preventable conditions | 3.4 | 1.3 | 2.6 | |

| Acute conditions | 21.3 | 10.6 | 2.0 | |

| Chronic conditions | 29.6 | 10.1 | 2.9 | |

| Victoria | Total PPH | 44.0 | 23.1 | 1.8 |

| Vaccine-preventable conditions | 4 | 1.5 | 2.7 | |

| Acute conditions | 16.9 | 10.6 | 1.6 | |

| Chronic conditions | 23.6 | 11.3 | 2.1 | |

| Queensland | Total PPH | 70.9 | 26.8 | 2.6 |

| Vaccine-preventable conditions | 6.3 | 1.4 | 4.5 | |

| Acute conditions | 30.8 | 13.5 | 2.3 | |

| Chronic conditions | 35.1 | 12.1 | 2.9 | |

| Western Australia | Total PPH | 92.5 | 22.6 | 4.1 |

| Vaccine-preventable conditions | 11.9 | 1 | 11.9 | |

| Acute conditions | 40.6 | 11.7 | 3.5 | |

| Chronic conditions | 42 | 10 | 4.2 | |

| South Australia | Total PPH | 73.7 | 24.1 | 3.1 |

| Vaccine-preventable conditions | 9.6 | 1.7 | 5.6 | |

| Acute conditions | 29 | 11.9 | 2.4 | |

| Chronic conditions | 36.8 | 10.8 | 3.4 | |

| Northern Territory | Total PPH | 117.1 | 26.8 | 4.4 |

| Vaccine-preventable conditions | 27.9 | 2.1 | 13.3 | |

| Acute conditions | 44.1 | 12.7 | 3.5 | |

| Chronic conditions | 52 | 12.3 | 4.2 | |

| Tasmania | Total PPH | 24.6 | 20.3 | 1.2 |

Note: PPH category types not reported for Tasmania.

PPH rates by Remoteness category

Within the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Performance Framework (Australian Health Ministers’ Advisory Council, 2017) PPH are also reported by remoteness for the years 2013 to 2015 (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2017). The rates for PPH were highest for Indigenous people living in Remote and Very Remote Australia, and lowest in the Inner Regional Australia and the Major Cities of Australia Remoteness categories (Table 3). Rates were higher for Indigenous Australians across all Remoteness categories compared to those for their non-Indigenous counterparts which were relatively equal across the Remoteness classifications.

| Remoteness Area | Potentially preventable hospitalisations rates for Indigenous Australians per 1,000 persons | Potentially preventable hospitalisations rates for Non-Indigenous Australians per 1,000 persons | Rate ratio of Indigenous to non-Indigenous Australians | Estimated Resident Population of Indigenous people (2016) |

| Remote Australia | 126 | 28 | 4.5 | 53,467 |

| Very Remote Australia | 109 | 29 | 3.8 | 95,415 |

| Outer Regional Australia | 72 | 26 | 2.8 | 165,879 |

| Inner Regional Australia | 49 | 24 | 2.0 | 186,131 |

| The Major Cities of Australia | 49 | 23 | 2.1 | 297,209 |

Table 4 provides a broad comparison contrasting the percentage of Indigenous PPHs in the Remoteness category against the percentage of the Indigenous population living in the Remoteness category for all states and the Northern Territory. For New South Wales, the relationships between the percentage of PPH in a Remoteness category compared to the percentage of population in the corresponding Remoteness category was less than a 1:1 ratio across all Remoteness categories. This result was also evident for Victoria indicating a fairly equal distribution of PPHs to population at this geographic classification (Remoteness category). For South and Western Australia, the percentage of PPH was higher in the Major Cities of Australia and the Outer Regional Australia Remoteness categories. This trend was also apparent in Queensland to a smaller extent, however, the percentage of PPH was higher than the percentage of population in the Inner Regional Australia Remoteness category. In the Northern Territory, the percentage of PPHs are higher across all Remoteness categories.

| The Major Cities of Australia | Inner Regional Australia | Outer Regional Australia | Remote Australia | Very Remote Australia | ||||||

| Percentage of category | PPH (%)# | Pop (%) | PPH (%)# | Pop (%) | PPH (%)# | Pop (%) | PPH (%)# | Pop (%) | PPH (%)# | Pop (%) |

| New South Wales | 36 | 41 | 47 | 49 | 21 | 25 | 10 | 12 | 2 | 4 |

| Victoria | 9 | 10 | 10 | 11 | 4 | 5 | >1 | <1 | n.a. | n.a. |

| Queensland | 28 | 25 | 32 | 25 | 41 | 38 | 23 | 24 | 17 | 25 |

| South Australia | 9 | 7 | 2 | 2 | 7 | 6 | 3 | 3 | 5 | 5 |

| Western Australia | 16 | 13 | 4 | 4 | 11 | 9 | 25 | 31 | 28 | 23 |

| Tasmania | n.a. | n.a. | 4 | 8 | 2 | 7 | >1 | 1 | >1 | >0 |

| Northern Territory | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | 14 | 11 | 38 | 29 | 49 | 44 |

Note: # Data taken from Public Health Information Development Unit, 2020.

The types of PPH associated with Indigenous Australians

There were geographical differences in the rates of admission for PPH conditions at the State and Territory level (Table 5).

- Convulsions and Epilepsy, and Cellulitis conditions were consistently ranked in the top five ranked PPH within the five regions for which data were available (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2017). Rates for Convulsions and Epilepsy varied from 3 per 1,000 people in Victoria, which was far below the National average (5.7), to 8.1 per 1,000 people in the Northern Territory. Similar geographic trends were found for Cellulitis.

- Rates of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD), when compared across all conditions, were highest in New South Wales, Victoria and Queensland. COPD was not a top five ranked condition in Western Australia.

- Rates of Dental conditions were somewhat comparable between Indigenous and Non-Indigenous people with New South Wales having lowest rates and Queensland the highest rates. Dental conditions were not reported as a top five ranked condition in Western Australia and the Northern Territory.

- Rates of diabetes complication in Queensland were over four times higher than those for non-Indigenous people. This condition was not reported as a top five ranked PPH condition in New South Wales and the Northern Territory.

- New South Wales had Ear, Nose and Throat (ENT) infection rates less than the national average while Western Australia and Northern Territory had higher rates than the national average. This condition was not reported as a top five ranked PPH condition in Victoria and Queensland.

- Rates for Other Vaccine-preventable conditions were nearly 17 times higher than non-Indigenous people in the Northern Territory.

| Australia | New South Wales | Victoria | Queensland | Western Australia | Northern Territory | |||||||

| Indigenous | Non-Indigenous | Indigenous | Non-Indigenous | Indigenous | Non-Indigenous | Indigenous | Non-Indigenous | Indigenous | Non-Indigenous | Indigenous | Non-Indigenous | |

| Convulsions and epilepsy | 5.7 | 1.4 | 4.7 | 1.4 | 3 | 1.3 | 5.7 | 1.7 | 7.6 | 1.1 | 8.1 | 1.4 |

| Cellulitis | 7 | 2.2 | 5.2 | 2.2 | 3.3 | 1.8 | 7.9 | 3 | 10.5 | 1.8 | 11 | 3.6 |

| Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD) | 11.1 | 2.3 | 11.3 | 2.3 | 7.9 | 2.1 | 10.7 | 2.6 | n.p. | n.p. | 16.1 | 3.6 |

| Dental conditions | 3.4 | 2.6 | 2.8 | 2.2 | 3 | 2.7 | 3.4 | 2.5 | n.p. | n.p. | n.p. | n.p. |

| Diabetes complications | 6.6 | 1.6 | n.p. | n.p. | 4.4 | 1.6 | 7.6 | 1.8 | 4.4 | 1.6 | n.p. | n.p. |

| Ear, Nose and Throat (ENT) infections | 3.2 | 1.6 | 2.6 | 1.6 | n.p. | n.p. | n.p. | n.p. | 4.3 | 1.5 | 5.6 | 1.6 |

| Other Vaccine-preventable | 6.1 | 0.8 | n.p. | n.p. | n.p. | n.p. | n.p. | n.p. | 9.2 | 0.6 | 21.9 | 1.3 |

Note: n.p. is not published as part of not being a top five ranked condition in the region.

The expenditure on PPH associated with Indigenous Australians

The expenditure on Indigenous PPHs was approximately $219 million in 2010–11 (most recent year of publication), or $385 per Indigenous person (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2013). This compares to $174 per non-Indigenous persons. Indigenous people had the highest level of per person expenditure at $202 per person for chronic conditions compared to $98 per person for non-Indigenous Australians. Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD) and diabetes complications were the highest contributors to these costs. Acute conditions were costed at $163 per Indigenous Australian compared to $71 for non-Indigenous Australians. Expenditure on Vaccine-preventable conditions was $21 per Indigenous Australians compared to $5 per non-Indigenous Australian.

Summary of the recent literature published on Potentially Preventable Hospitalisations for Indigenous Australians by State and Territory

Potentially Preventable Hospitalisations for Indigenous Australians in New South Wales

New South Wales has around 33% of the total Indigenous population (265,685 persons) representing 3% of the total New South Wales population. Around 46% in live in the Major Cities of Australia Remoteness category, 34% in the Inner Regional Australia, 16% in the Outer Regional Australia, 2% in the Remote Australia and 1% in the Very Remote Australia Remoteness categories (Australian Bureau of Statistics 2018a).

Duncan et al. (2013) found from analysing presentations to the Sydney Children’s Hospital emergency department between 2002 to 2008 that Indigenous children aged 0-15 years presented more often than other Australians and were over-represented in the emergency department population. Overall 44% of presentations by Indigenous children were coded potentially preventable and could have been avoided. Many presentations were in children less than one year old and presentations reduced as age increased. Less than half (46%) of the children presented only once, 37% presented two to four times and 17% presented more than five times. The authors highlighted that the more frequent or multiple presenters to the emergency department did not represent children with a greater severity of illness or chronic disease and could have been treated in a community setting.

Harrold et al. (2014) investigated 987,604 admissions for PPH conditions of which 3.7% were for Indigenous people over 2003/04 to 2007/08. The overall age-standardised rate of PPH admissions for Indigenous people was 76.5 per 1,000 persons compared with 27.3 per 1,000 persons for non-Indigenous people, a ratio of 2.80. Significantly higher rates of PPH admissions for Indigenous people were found for all PPH conditions, with the exception of nutritional deficiencies (for which numbers were very small). The study found that diabetes complications were responsible for the largest disparity with the rate being more than five times higher than for non-Indigenous people of the same age-group, sex and area of residence. A major outcome of this study was determining that 30 Statistical Local Areas in NSW had high rates as well as high disparity (calculated as a high disparity of rates between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians) with the majority in regional areas. Conversely, the study highlighted three Statistical Local Areas with of low rates and low disparities.

Falster et al. (2016) investigated a state-wide cohort of children born in New South Wales from 2000 to 2012, reporting over 365,000 potentially avoidable hospitalisation. Rates for Indigenous children were 90.1 per 1,000 person-years and 44.9 per 1,000 person-years for non-Indigenous children. Rate differences and rate ratios (difference between Indigenous and non-Indigenous rates) declined with age, 94 per 1,000 person-years and 1.9 for children less than two years to 5 per 1,000 person-years and 1.8 for ages 12-14 years. Avoidable hospitalisations rates were almost double in Indigenous children who were less than two years of age compared with non-Indigenous children of the same age. Respiratory and infectious conditions were the most common reasons for avoidable hospitalisations in all children, although Indigenous children were admitted more frequently for all conditions. Non-avoidable hospitalisations rates were almost identical between Indigenous and non-Indigenous children. The study also investigated the effect of remoteness and found a greater impact on children living in more remote areas, with a child’s risk of avoidable hospitalisation greater for Indigenous children. For example, Indigenous children living in the remote areas and major city categories were 2.2 and 1.5 times more likely to be admitted for an avoidable hospitalisation than non-Indigenous children living in the major city classification. In contrast, non-Indigenous children living in remote areas were 1.1 times more likely to be admitted for an avoidable hospitalisation when compared to non-Indigenous children living the major city classification. The increasing trend in rate ratios suggests that there was a difference in PPH rates for children by remoteness in New South Wales.

Potentially Preventable Hospitalisations for Indigenous Australians in Queensland

Queensland has around 28% of the total Indigenous Population (221,276 persons) representing 5% of the total Queensland population. Around 34% live in the Major Cities of Australia Remoteness category, 21% in the Inner Regional Australia, 28% in the Outer Regional Australia, 6% in the Remote Australia and 11% in the Very Remote Australia Remoteness categories (Australian Bureau of Statistics 2018a).

Harriss et al. (2018) investigated admissions to a regional north Queensland hospital with a local catchment area of 10 Statistical Local Areas. A total of 29,485 local residents generated 51,087 separations of which 5,488 (11%) were PPHs. Around 76% of all PPH were either chronic conditions or acute conditions associated with chronic conditions. Age-standardised PPH rates were 3.4 times higher for Indigenous than non-Indigenous people. Indigenous people made up 25% of these admissions and an estimated 37% of the total cost of total PPHs. The median cost estimated for Diabetes complications for Indigenous people was $11,546. This compared to $4,887 for non-Indigenous Australians. Although relatively low rates of Vaccine-preventable PPHs were observed, the rate of these PPHs for Indigenous people was nearly eight times higher than for non-Indigenous people. The authors highlight that the financial costs associated with PPH were substantially higher for Indigenous people, and these higher costs justify investment in strategic, collaborative, evidence-based primary health interventions aimed at addressing health inequalities experienced in northern Queensland.

Another study (Caffery et al. 2017) highlighted the prevalence of dental conditions in the Indigenous populations from all Queensland public and private hospital patients between 2011 and 2013. Indigenous infants and primary school children were significantly more likely to be hospitalised due to oral and dental conditions than their non-Indigenous counterparts. They found lower rates of hospitalisations for high school children but no significant difference in the rate of hospitalisation for adults.

Potentially Preventable Hospitalisations for Indigenous Australians in Western Australia

Western Australia has around 13% of the total Indigenous population (100,512 persons) representing 4% of the total Western Australian population. Around 40% live in the Major Cities of Australia Remoteness category, 8% in the Inner Regional Australia, 14% in the Outer Regional Australia, 17% in the Remote Australia and 22% in the Very Remote Australia Remoteness categories (Australian Bureau of Statistics 2018a).

Following on from the Grattan Institute report on PPH hotspots (Duckett and Griffiths 2016), Gavidia et al. (2019) undertook a state-based PPH hotspot analysis across Western Australia for the years 2010-11 to 2015-2016. The findings showed that areas with larger Indigenous populations were more likely to qualify as hotspots, especially for Acute conditions. This relationship did not hold for convulsions and epilepsy and dental conditions. When all 22 conditions were analysed together the Kimberley region was highlighted as a significant hotspot standing apart from the rest of Western Australia.

Western Australia has a long history in the investigation of dental conditions, especially reporting on the disparities between Indigenous and non-Indigenous children (Slack-Smith et al. 2011; Slack-Smith et al. 2013). Recent work by Kruger and Tennant (2015) over a ten-year period between 1999-2000 to 2008-2009 found that Indigenous PPH admission rates for oral health conditions increased over time at a rate almost twice that of non-Indigenous people. Alsharif et al. (2015) analysing a similar time period of hospitalisations for children under 15 years of age also showed this trend with the age-standardised rates of hospitalisation in the last decade increasing to reach that of non-Indigenous children in 2009. The length of stay was found to be longer for Indigenous children. Remoteness differences were also found with rural-living non-Indigenous children having 1.2 times the admission rate of rural-living Indigenous children. In contrast, Indigenous children living in major cities or regional areas had 2.6 times the admission rate of their Indigenous counterparts in rural or remote areas. Geographical access to health services was considered as the reason for this unequal distribution by the authors stating that Indigenous children in metropolitan areas were more likely to be admitted than Indigenous children in rural areas and all were less likely to have private health insurance cover which provides a role in health service delivery. The authors state that hospitalisations for ‘pulp and periapical’ conditions were mainly due to periapical abscess without sinus formation and that uninsured, Australian Indigenous male children aged less than nine years, and living in the most disadvantaged areas were more likely to be admitted for this condition. This indicates that they only access dental care when conditions have reached this advanced stage.

Of significance was research undertaken by Ha et al. (2019) in which a metric to understand the coverage or continuity of care was created for a cohort of people 45 years and over with diabetes mellitus. The measure was based on the maximum time interval between general practitioner visits that afforded a protective effect against avoidable hospitalisations across the cohorts. The metric of coverage or continuity of care was found to be lowest for Indigenous people.

Potentially Preventable Hospitalisations for Indigenous Australians in the Northern Territory

The Northern Territory has around 9% of the total Indigenous population (74,546 persons), equating to 30% of the total Northern Territory population. Around 23% of the population live in the Outer Regional Australia Remoteness category (largely Darwin), 21% in the Remote Australia and 56% in the Very Remote Australia categories (Australian Bureau of Statistics 2018a). Socioeconomic disadvantage is a major driver of ill-health with 25-30% of the NT health disparity explained by socioeconomic disadvantage (Zhao et al. 2013).

Early research by Li et al. (2009) found that, in the years 1998-99 to 2005-06, avoidable hospitalisations made up 15.6% of total hospitalisations. Indigenous people made up 61% of these hospitalisations while only making up 28% of the population at the time of publication. Rates of avoidable hospitalisations were estimated at 11,090 per 100,000 population, nearly four times the Australian rate of 2,848 per 100,000 population. Rates of Indigenous PPH exceeded the Australian rates for almost all conditions with the highest rate ratios for nutritional deficiencies (19.7), diabetes complications (6.8) and influenza and pneumonia (6.1).

Later studies have concentrated on populations within remote communities reporting that there were gaps in screening and the recognition of elevated cardiovascular disease (Burgess et al. 2011) as well as a high proportion of individuals who were at a high risk of diabetes and had an accentuated cardiovascular risk profile (Arnold et al. 2016). Zhao et al. (2013b) explored the relationship between primary health care utilisation and hospitalisations by linking 52,739 Indigenous residents from 54 remote primary care clinics and five public hospitals for the years between 2007 and 2011. This population was characterised as having a high health need, high hospitalisation rate and poor access to primary health care. Across all conditions and demographic groups, they found a U-shape relationship between primary health care visits and hospitalisations. This result translates into an inverse association i.e. hospitalisations decrease as the number of primary care visits increase up to a certain (optimal) point (less than four primary health care visits) from which there was a positive association (i.e. hospitalisations increase as visits increase) with visits greater than four. The data also showed that people who did not access primary health care services at all in the previous 12 months were more likely to be hospitalised. For specific conditions like diabetes and ischaemic heart disease (Angina), the minimum level of hospitalisation was calculated when there were 20–30 visits a year while for children with dental conditions, the number of visits was estimated at 5–8 per year.

Thomas et al. (2014) reporting on a 14,184 patient cohort collected between 2002 and 2011 of Indigenous residents aged 15 and over with diabetes who attended one of five hospitals or 54 remote clinics reported that improving access to primary care in remote communities for the management of diabetes resulted in net health benefits to patients and cost savings to the government. They showed that compared to the low primary care use group, those that had medium usage (2-11 times annually) had lower PPH rates. Among complicated cases the rate of PPH was 0.72 per 100 population compared to 3.64 per person. Thomas et al. (2014) report that the cost of preventing one hospitalisation for diabetes was $248 for those in the medium-use group and $739 for those in the high-use group. This compares to $2915, the average cost of one hospitalisation.

Further analysis of the dataset (Zhao et al. 2015) reported a similar U-shaped curve for patients with diabetes where all-cause hospitalisations were minimised when primary health care visits were 7.9 per person-years (95% Confidence Interval 5.8-10). The authors propose that the effectiveness of a health system may hinge on a refined balance, rather than a straight-line relationship between primary health care and tertiary care in this area. Undertaking an investigation into chronic disease management, Zhao et al. (2014) also found a decrease in avoidable hospitalisation with increasing primary health care in 14,184 Indigenous residents, aged 15 years and over, who lived in remote communities and used a remote clinic or public hospital from 2002 to 2011. Compared to patients in the low primary care utilisation group, PPH rates in the medium (2-11 visits per year) and high primary care (12 visits or more per year) groups were 76% and 80% lower, respectively, for diabetes, 63% and 78% for ischaemic heart disease (Angina) and, 70% and 78% for hypertension. For chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), the reduction in the rate of PPH was the same for the both medium and high primary care groups (60%). In terms of cost-effectiveness, primary care for diabetes ranked as more cost-effective, followed by hypertension and ischaemic heart disease. Primary care for COPD was the least cost-effective of the five conditions. Primary care in remote Indigenous communities was shown to be associated with cost-savings to public hospitals and health benefits to individual patients. Investing $1 in high and medium level primary care in remote Indigenous communities could save between $3.95 and $11.75, respectively, in hospital costs, in addition to health benefits for individual patients.

Potentially Preventable Hospitalisations for Indigenous Australians in South Australia

South Australia has around 5% of the total Indigenous Population (21,957 persons) and this represents around 2.5% of the total South Australian population. Around 52% live in the Major Cities of Australia Remoteness category, 9% in the Inner Regional Australia, 24% in the Outer Regional Australia , 4% in the Remote Australia and 11% in the Very Remote Australia Remoteness categories (Australian Bureau of Statistics 2018a).

Early research (Banham et al. 2010) on South Australian residents in the years 2006 to 2008 identified that Indigenous people were part of a vulnerable population that were more likely to have more than one preventable admission. Research (Banham et al. 2017) on chronic PPH conditions for the years 2005-06 to 2010-11 across the majority of South Australia identified a social gradient for Indigenous people by area disadvantage and Remoteness categories, with the length of stay and financial cost increasing with increasing disadvantage and remoteness. This gradient also existed for the non-Indigenous population, however, the slope of this gradient was lower. Associated hospital costs were found to be 50% higher than that for non-Indigenous patients on average and to be more variable within the group of Indigenous patients. Disparities existed for Indigenous people with higher risks of chronic PPH hospitalisations with crude rates of 11.5 per 1,000 population compared to the non-Indigenous rate of 6.2 per 1,000 population. Diabetes complications were nearly 4 times (4.3 per 1,000 versus 1.3 per 1,000) the rates for non-Indigenous people. Of those that were hospitalised, Indigenous Australians were found to be younger than non-Indigenous people (median age of 48 years versus 70 years). Indigenous Australians were also found to have a higher number of admissions, 2.6 versus 1.9 per person, a longer total length of stay (11.7 versus 9.0 days) and higher average hospital costs ($A17,928 vs $A11,515 per person) when compared to non-Indigenous Australians. Of note is that data from the Anangu Pitjantjatjara Yankunytjatjara (APY) lands was not included in the analysis. This equated to around 2,000 Indigenous people (around 9% of South Australian Indigenous population) who live in the Very Remote Australia Remoteness category.

Banham et al. (2019) investigating metropolitan emergency department presentations for ambulatory care sensitive conditions (i.e. PPH conditions) and GP-type issues between 2005-06 to 2010-11 found that adult Indigenous people had a greater presentation rate, 154.6 per 1,000 population when compared with 71.7 per 1,000 population for a comparable non-Indigenous population. Rates of presentation were higher for Acute conditions for Indigenous people (125.8 per 1,000 population compared to 51.6 per 1,000 population) and also for Chronic conditions (41.6 per 1,000 population compared to 21.1 per 1,000 population). Rates for Vaccine-preventable conditions were similar for both Indigenous and the comparator group (3.6 per 1,000 population vs 3.3 per 1,000 population). Rates for GP-type presentations were also higher for Indigenous Australians with 308 presentations per 1,000 population versus 240 presentations per 1,000 population for the non-Indigenous group. These higher rates equated to an excess cost of $108,000 per 1,000 population for Acute conditions and $53,000 per 1,000 population for Chronic conditions. Indigenous people were also found to have had higher multiple attendances when compared to the comparator group. For example, a total of 5,095 Indigenous persons presented 23,825 times to the emergency department, 40% of these persons had one presentation, 16.7% presented twice, 16.9% had three or four presentations, and 26.4% had five or more presentations. This compares to the non-Indigenous comparison group where 346,844 persons had 898,399 presentations of which 52.6% had one presentation, 19.8% had two presentations, 15.3% had three or four presentations and 12.2% had five or more presentations.

Data and methodology

Users are directed to the notes below under Data for Indigenous Areas (IAREs) to be used with caution, because of issues impacting on the quality of the data and analysis, including the under-identification of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people in the hospitalisation data, the varaition in the quality of geo-coding, the relatively small number of cases both overall and by category and condition when analysed at the IARE level, and variability between years in the number of admissions.

Hospital admission data

PPH data were provided to the Public Health Information Development Unit by the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, on behalf of the state and territory health departments, from the National Hospital Morbidity Database for the five years 2012-13 to 2016-17. These data have been published previously by the Public Health Information Development Unit on an annual basis. Records where age group and area of residence were not reported were removed from the analysis. The dataset comprised of all individual Indigenous patient admissions to all private and public acute hospitals, a total of 2,225,287 records. The Australian Institute of Health and Welfare report Indigenous identification in hospital separations data: quality report estimated that, in the 2011–12 study period, about 88% of Indigenous Australians were identified correctly in public hospital admissions data (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2013). It is unknown to what extent Indigenous Australians might be under-identified in private hospital admissions data.

A total of 179,601 records were flagged as potentially preventable conditions (Table 6) accounting for around 8% of all Indigenous hospital admissions, a rate that was stable over the five years of data. PPHs were defined in accordance with the Council of Australian Governments’ National Healthcare Agreement PI 18 – Selected potentially preventable hospitalisations, 2018 (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2018b). The Agreement identifies 22 PPH categories but we have removed the female-specific conditions of Eclampsia and Pelvic Inflammatory Disease to focus on population-based conditions only.

For Indigenous Australians, the Acute PPH category of conditions made up 51% of admissions, 40% were recorded as Chronic PPH category and nine percent were reported as Vaccine-preventable PPH category conditions over the five-year period. The percentage composition of admissions by specific PPH conditions were Angina (4.2% of all PPHs), Asthma (4.9%), Bronchiectasis (1.4%), Cellulitis (11.8%), Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD) (10.6%), Congestive Cardiac Failure (CCF)(5%), Convulsions and Epilepsy (10.1%), Dental Conditions (8.9%), Diabetes complications (8.1%), Ear, Nose and Throat Infections (ENT) (8.7%), Gangrene (2.2%), Hypertension (<1%), Iron Deficiency Anaemia (3.2%), Nutritional Deficiencies (<1%), Rheumatic Heart Diseases (1.6%), Urinary Tract Infections (UTI) (8.6%), Perforated/Bleeding Ulcer (<1%), Pneumonia and Influenza (Vaccine-preventable) (3.0%), Pneumonia (Not Vaccine-preventable) (<1%) and Other Vaccine-preventable conditions (6.3%).

PPH admissions were further differentiated into three hospital admission types, Total, Same-Day and Overnight admissions (Table 6). This differentiation was used to identify hospitalisations where the condition of the patient was less or more severe. Analysis of the Indigenous admissions showed that Same-Day admission made up 27% or 47,689 of all PPH admissions. For the Acute PPH category, 32% of admissions were Same-Day with the majority (39%) being admissions for Dental conditions (n = 11,569). These admissions were more than double that of the next highest Acute conditions; Convulsions and Epilepsy (n = 5,753) and Ear, Nose and Throat (ENT) (n = 5,308). Same-Day admissions were lower for the Chronic PPHs category (22%) and more evenly distributed amongst the condition types with 27% of these admissions being for Iron Deficiency Anaemia (n = 4,311). Once again these were double the Same-Day admission for Diabetes Complications (n = 2,553), Angina (n = 2,333), and Asthma (n = 2,264).

A total of 131,912 Overnight admissions, nearly half of which were for Acute conditions, far outweighed the number of Same-Day PPH admissions. Within each PPH category, Overnight admissions comprised a large proportion, with 68%, 78% and 84% of total admissions for the Acute, Chronic and Vaccine-preventable PPH categories, respectively being Overnight admissions. Three conditions, Cellulitis, Convulsions and Epilepsy and Urinary Tract Infections made up 69% of Overnight admissions for the Acute PPH category. COPD and Diabetes Complication conditions made up just over half (52%) of the Overnight admissions for the Chronic PPH category.

| Potentially Preventable Hospitalisation (PPH) | Same-day Separations | Overnight Separations | Total |

| Acute | 29,380 | 61,756 | 91,136 |

| Urinary Tract Infection | 2,977 | 12,429 | 15,406 |

| Dental conditions | 11,569 | 4,330 | 15,899 |

| Cellulitis | 3,470 | 17,676 | 21,146 |

| Ear, Nose and Throat Infections | 5,308 | 10,238 | 15,546 |

| Convulsions and Epilepsy | 5,753 | 12,362 | 18,115 |

| Gangrene | 236 | 3,640 | 3,876 |

| Perforated or Bleeding Ulcer | 53 | 619 | 670 |

| Pneumonia and Influenza (Non-Vaccine Preventable) | 14 | 464 | 478 |

| Chronic | 15,572 | 56,235 | 71,807 |

| Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD) | 1,917 | 17,159 | 19,076 |

| Congestive Cardiac Failure (CCF) | 955 | 8,037 | 8,992 |

| Iron Deficiency Anaemia | 4,311 | 1,470 | 5,781 |

| Diabetes complications | 2,553 | 12,069 | 14,622 |

| Angina | 2,333 | 5,140 | 7,473 |

| Asthma | 2,264 | 6,563 | 8,827 |

| Hypertension | 365 | 1,133 | 1,495 |

| Bronchietasis | 346 | 2,194 | 2,540 |

| Rheumatic Heart Disease | 524 | 2,295 | 2,819 |

| Nutritional Deficiencies | 4 | 175 | 179 |

| Vaccine-preventable | 2,797 | 13,921 | 16,658 |

| Pneumonia and Influenze (Vaccine-preventable only) | 313 | 5,105 | 5,418 |

| Other Vaccine-preventable conditions | 2,424 | 8,816 | 11,240 |

| Total PPH | 47,689 | 131,912 | 179,601 |

The small numbers of separations for many conditions and when analysed by separation type, particularly Same-Day separations, meant that we only created geographic information for conditions where the number of observations was adequate to provide a reasonable coverage at the IARE level across Australia. The 17 datasets that were analysed are shown in Table 7.

| Hospital Separation Type | Datasets Analysed |

| Total, Same-Day and Overnight Separation | Total, Chronic and Acute PPH categories |

| Total Separations | Vaccine-preventable PPH category, Cellulitis, Convulsions and Epilepsy, Dental conditions, Ear, Nose and Throat (ENT), Urinary tract Infections (UTI), Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD), and Diabetes complications |

Indigenous Areas (IAREs)

The geographic representation of the Indigenous PPH data is through the Australian Bureau of Statistics Indigenous Area (IARE) geography (Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2016a). IAREs are medium sized geographical units designed by the Australian Bureau of Statistics to facilitate the release and analysis of detailed statistics for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people. IAREs provide a balance between spatial resolution and population size and are designed for the purpose of disseminating more detailed socio-economic attribute data than is available for the Indigenous Locations (the smallest geographical area for which the Australian Bureau of Statistics releases data about Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people).

Data for Indigenous Areas (IAREs) to be used with caution

These data should be used with caution for a number of reasons, including:

- under-identification of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people in the hospitalisation data;

- the variation in the quality of geographically coding where a person lives

- the small number of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people living in some IAREs;

- the relatively small number of cases overall and by category and condition when analysed at the IARE level; and the

- variability between years in the number of admissions.

This caution is of particular relevance to the Vaccine-preventable PPH category, due to changes in coding from 2013-14 which resulted in an apparent rise in Hepatitis B (Australian Health Ministers’ Advisory Council, 2017). This is reflected in the Other Vaccine-preventable conditions data in Table 8 with over three times more cases in 2013-14 than in 2012-13.

| Vaccine-preventable conditions | 2012-2013 | 2013-2014 | 2014-2015 | 2015-2016 | 2016-2017 | Total |

| Pneumonia and Influenza (Vaccine-preventable only) | 978 | 733 | 1,108 | 1,155 | 1,444 | 5,418 |

| Other Vaccine-preventable conditions | 599 | 2,273 | 2,597 | 2,813 | 2,958 | 11,240 |

| Total | 1,577 | 3,006 | 3,705 | 3,968 | 4,402 | 16,658 |

The data for Pneumonia and Influenza (Vaccine-preventable only) in Table 8 also highlight the yearly fluctuations in admissions; and while these fluctuations will occur, the chosen methodology predicates that the numbers of admissions within an IARE do not change too erratically over time. To understand the magnitude of annual change in admissions at the IARE geography, the annual trends in non-PPH admissions within each IARE was investigated as the number of admissions per IARE was larger. Given that there was five years of data available, a conservative approach to screening IAREs for what we considered was reliable data was undertaken. The first step involved identifying a list of IAREs where the percentage increments between consecutive years were within ±30%; and of those IAREs where this threshold was exceeded. Given that the annual percentage change can be large for IAREs with lower numbers of admissions, the data was iteratively screened to flag what were considered unreliable increases. A total of 156 IAREs were flagged as “IAREs to be used with caution” because of what we consider are data reliability issues (Table 9). It is hard to conclude why these fluctuations occur; an example may be a change in the way these admissions were geo-coded to the IARE geography from the previous year. This issue needs to be flagged to the user and as such a flag has been created within the Atlas to identify which IARE has issues with data reliability.

| State/Territory | Number and Percentage of flagged IARE |

| New South Wales | 29 (19%) |

| Victoria | 25 (16%) |

| Queensland | 23 (15%) |

| South Australia | 9 (6%) |

| Western Australia | 33 (21%) |

| Tasmania | 4 (3%) |

| Australian Capital Territory | 1 (1%) |

| Northern Territory | 32 (21%) |

| Total | 156 |

Population Data

Population data are needed for the calculation of rates. However, annual data on Indigenous populations by IARE are limited, especially past estimates. This situation therefore requires estimates to be compiled from the Indigenous population data available. A further restriction on data availability is that there is a substantial difference between the total counts reported in the 2016 Census and the total estimated resident population (ERP) of Indigenous Australians which is adjusted by the Australian Bureau of Statistics for net undercount as measured by the Post Enumeration Survey. This means that the total ERP for Indigenous Australians is 17.5% higher than the corresponding Census count. Given this difference, and as the Australian Bureau of Statistics has not released Indigenous ERP by age at the IARE geography, ERP estimates for the Indigenous populations by IARE had to be modelled.

Several datasets were available for the year 2016 which provided the starting point for the creation of annual Indigenous populations by IARE.